« on: October 21, 2017, 12:08:22 AM »

To Adventure?

The World Of Adventure Game Design

By Jubal

This week's Exilian Article, brought to you by Tiny Bertrella Slugkin.

This week's Exilian Article, brought to you by Tiny Bertrella Slugkin.

What are these? Firstly and most importantly, adventure games tend to have inventories, object interaction, and puzzles. These form the core of the gameplay, which is mainly about puzzle solving: enemies are there to be avoided or tricked, rather than destroyed by a more militarily powerful player. In general a classic adventure game has no consistent/regularly used combat mechanic; the aim is to work through all the different puzzles (or some of them, in branching or open-world adventures) in order to complete the game. This in turn is part of what gives adventure games their specific feel - the lead character is rarely a combat-heavy or powerful figure (or if they are, as with the lead of the early King's Quest games, they are put in situations where this is of little use to them). This strongly differentiates them from RPGs, which tend to involve heroes who have the combat abilities to directly take on enemies. Many adventure games have a fairly clear plotline, even if there are choices as to exactly how it unfolds in different versions. Death is usually not a major issue or severely punished, though this can vary.

Another theme of adventure games that it's worth mentioning is light-heartedness. One can make dark point and clicks, of course, especially if they're escape the room type puzzles, but they're somewhat limited in scope; object-interaction gameplay, plus a physically weak character, plus a lot of easier task/puzzle ideas needing character interaction, all add up to it being easier to make adventure games in a chatty, talkative setting. Dark adventure games risk leaning too heavily into other mechanics, and for good reason: if you're in a war-zone, or a house with zombies in it, you're going to need to either spend vast amounts of time sneaking or give the character weapon abilities, both of which dilute the core mechanical theme of the genre.

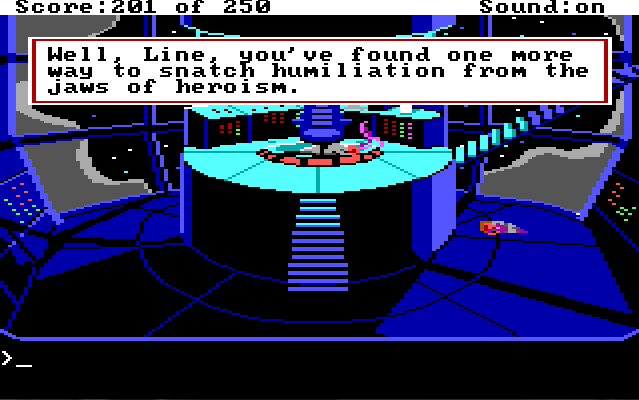

Space Quest: the snarky parser perfected?

Space Quest: the snarky parser perfected?

The difficulty of providing high variation (and thus replayability) and the problems of massively multifaceted object interactions are elements that may put some developers off the adventure genre, and indeed there are very few story-driven adventure games coming out of bigger studios nowadays - they're a feature of hobbyist and indie gaming markets primarily. When bigger designers do make adventure games, they often try to rely on non-adventure gaming mechanics, with disastrous results - the Matt Smith era Doctor Who adventure games being a very particular case in point, where many games relied purely on the "sneak" mechanic plus a few minigames. Doctor Who is the sort of setting that could be great for adventure gaming, but without the sort of classic object-interaction and character-interaction puzzles that make up traditional adventure games the recent DW series felt a bit flat.

So, we've talked a bit about adventure games, what makes them distinctive, and I've introduced a (very brief) summary of the genre's development. What are some things to think about when making adventure games?- Puzzles. A good adventure game needs good puzzles! I think this is a genuinely hard element, especially if you want to appeal to both genre-savvy players who will have high expectations of what they might be able to combine, and newer players who may get stuck more easily with object interaction. This is one reason I like the idea of putting in secondary routes through the game that use items/characters in more unexpected ways. One thing that's emerged in gaming since the golden era of adventure gaming is achievement systems, which are BRILLIANT when combined with multiple-route games, as they encourage players back to try and find the more hidden routes.

- Place. That is to say, both the setting of the adventure, the position of the character with regard to that setting, and the position of the player with regard to their character. Is the adventure something where you want the player to feel very strongly that they are the character, or something where they are telling the character's story? Will speech be reported, making more of a storyline feel, or direct, making things more close to hand?

- Playtesting. Adventure games probably require more testing than most genres, because the player has a large but limited set of options. Object types are usually fairly unique in adventure games and players expect to be combining them and thinking outside the box, unlike RPGs where actually despite a wider range of inventory possibilities there's a limited range of types of item each of which has one clear use (food, armour, weapon, weapon supplies, maaaybe potions/potion making kit). I don't think there's any better way to do out of the box testing than with real players.

Who knows where your game could end up? Mine ended up with an adipose in a forklift.**I am not legally responsible if your adventure also leads to inappropriately qualified aliens in charge of industrial vehicles and machinery.

Who knows where your game could end up? Mine ended up with an adipose in a forklift.**I am not legally responsible if your adventure also leads to inappropriately qualified aliens in charge of industrial vehicles and machinery.

I hope this has been a good overview of some of the history, problems and ideas around adventure games - in future articles I'd like to go more specifically into how to design particular puzzle mechanics and settings that will work well with the genre (not least because I have a lot of game ideas that I'm never going to get done myself, so throwing them at other people is the best chance they have, in what may become a sort of bizarre orphanage for game themes). I love playing adventure games, and if you've got one that I haven't tried then I'd love to see what other people are coming up with!

I do think that there's a lot to be said for adventure games as a genre - their history of light-heartedness and the easy ways in which observational humour and satire can be worked into the genre make them the perfect antidote at times like the present when the world is all too grimdark. They allow for strong interactions and character crafting compared to many RPGs & combat adventures where the story is often something that has to be packed around the gameplay rather than driving it. Getting started making simple adventures isn't hard - why not give it a go yourself? You never know where you might end up!

Logged

The duke, the wanderer, the philosopher, the mariner, the warrior, the strategist, the storyteller, the wizard, the wayfarer...