A Cartload of Cartography 2: Beyond the Middle Ages

September 23, 2018, 01:46:54 PM

By Tar-Palantir

Welcome to the second part of this series, on Early Modern maps! You can check the first part, on ancient to medieval maps, out here.

1. Eight leaves of the Catalan Atlas, from 1375.

Once we hit the 15th century, something a bit more like the modern map hoves into view. This is largely driven by advances in seafaring, spearheaded by Portugal and the Catalans. As long-distance voyages became more common, especially ones that involved potentially being out-of-sight of land for a while, actually accurate maps became more important. People could measure latitude pretty well by this point, as the astrolabe began to be replaced by the cross-staff and then the backstaff, making the measurement relatively accurate and simple. However, longitude was still problematic, as its accurate measurement relies on being able to accurately measure time, which was beginning to be resolved on land with better timepieces, but was still impossible at sea, as mechanical devices quickly accumulated error due to the motion of the ship and the excess of water and salt throwing out their delicate mechanisms. The alternative was dead reckoning, where you measure the distance you've sailed on a given bearing to plot your course. This works fairly well in sight of land, where you can correct against known coastal features, but, in the open ocean or along unfamiliar coasts, rapidly becomes inaccurate. Hence, maps from this period tend to look fairly decent in a north-south direction, but get east-west ones often quite wrong – Africa, for instance, usually ends up looking much wider than it actually is.

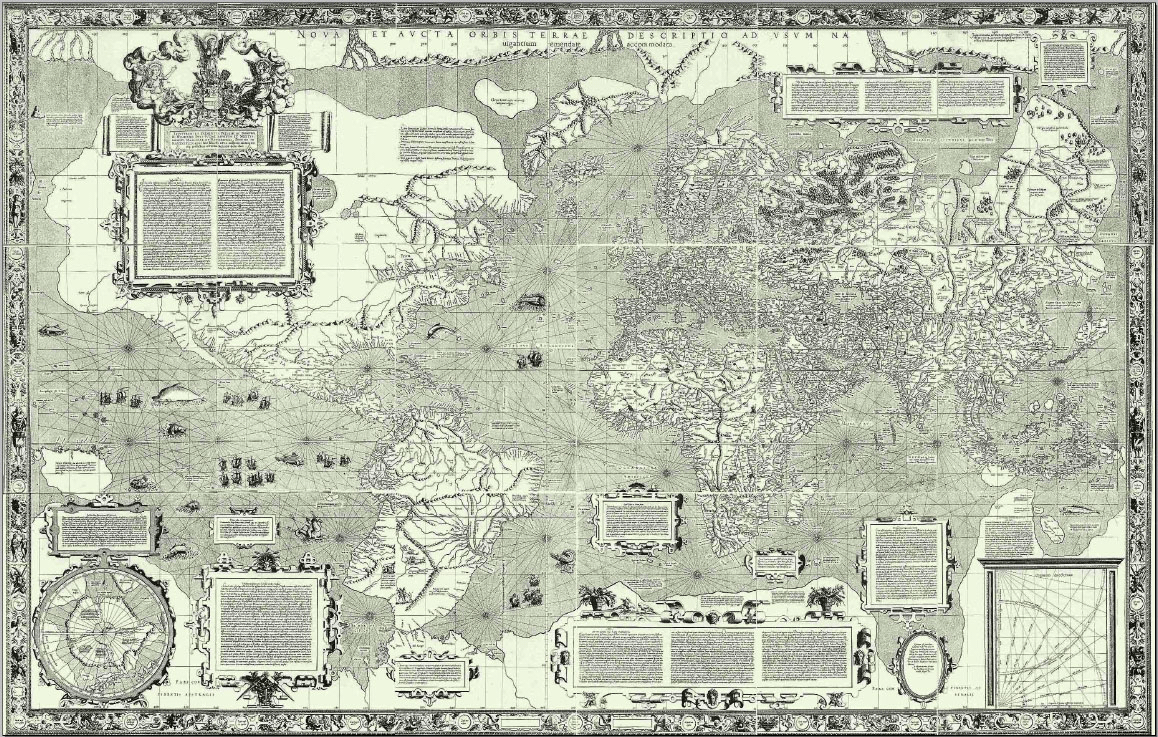

2. Mercator's map, 1569. Public domain via Wikipedia.

The late-14th century Catalan Atlas (Figure 1) is perhaps the most impressive map of this kind - the Mediterranean basin is rendered with a high level of accuracy, but as you move farther afield, this accuracy begins to wane. This map also draws very heavily on the mappa mundi tradition, with various myths and legends depicted in its farther-flung reaches. Most portolan charts were far less elaborate and only showed outlines of coasts with coastal towns and features named.

Portolan charts were produced for a specific purpose for a specific group of people and new ones were usually treated as state secrets, so weren't available to the general public. However, a more enquiring attitude to the world, overseas exploration (primarily for trade at this stage, not empire) and increasing rejection of Catholic dogma, also meant geographical information was more sought after by non-mariners, so we see the first atlases compiled; the very first, titled simply Atlas, including a world map (Figure 2) by Mercator in 1569, marking a shift in European cartographic power to the Netherlands. The work associated with the Netherlandish school of cartography is much closer to what we would think of as maps – they're meant to be repositories of geographic knowledge and, as far as possible, an accurate representation of the world. The culmination of this tradition is perhaps Joan Blaeu's Atlas Maior (Figure 3), published in 9-12 volumes, depending on the edition, between 1662 and 1672. As can be seen in Figures 2 and 3, this school of mapmaking has largely banished the medieval penchant for putting in all kinds of legendary creatures and features, contenting itself with some ships sailing on the sea, explanatory text and decorated borders. Useful bits of cartographic furniture, such as scale bars, also start to make an appearance, in keeping with the changed purpose of these maps.

4. A double hemisphere map, 1666. Boston Public Library.

Remember, though, there were still large parts of the world essentially unknown to European mapmakers at this stage – the interior of Africa and parts of Asia hadn't been nailed down yet. The outline of South America was fairly well-established, though its interior was, likewise, still largely conjectured. North America was less well-outlined, explorers having not yet reached the north-western coast, and the barest outlines of Australia and New Zealand only began to come in during the 17th century. Whilst the overt filling of spaces with legendary figures was no longer practised, mapmakers weren't averse to conjuring up mountains and rivers to fill them in in a slightly more naturalistic manner, so there was still room for invention.

Overall, then, you have a wide choice of map types if you want to set something in this sort of period. You could come up with something pretty medieval-looking overlaid on a somewhat-accurate topography; you could consider a very minimalist portolan chart, or you could move towards a grandly-decorated modern-style map. Think about what would likely to have been driving cartographic progress in your world and how that would affect the evolution of charts – would it be nautically driven, as in our world, or would something else be the main force?

Game Design's Ultimate Challenge

August 31, 2018, 10:05:08 PM

We've got our Colossus!

Pity we can't hit back at those bullies with slings...

(Painting: Salvador Dali)

By rbuxton

There are few things harder than compressing the entirety of human history into a video game, and one of them is compressing it into a board game. An example of this is A New Dawn, the latest board game adaptation of the epic Civilization series. In order to meet the Ultimate Challenge, the designers had made sacrifices: retaining the video game's random world generation had come at the expense (in my opinion) of any interaction with the world's oceans. I was disappointed with the absence of naval combat, but how would I have included it alongside a modular board?

I decided to make the tiles of the modular board as simple as possible: a single hexagon providing a given resource (wood, oil etc.). I used concentric hexagons to further divide the tile into three "tiers" - controlling all three would be necessary to gain the resource. Investing in new resources would slow down a player's exploration of the board, represented by flipping tiles over. The modular board would, coincidentally, resemble Catan's.

Next, I needed a single mechanic to simulate nations' military, scientific and cultural advances. I turned to deck building (hold cards, play cards, draw better cards, repeat) and gave players the Hunting (for movement) and Gathering (for recruiting troops) cards at the start of the game. Instead of playing cards, they could "scoop" all of their played cards back into their hand and choose a new one (representing a scientific advance). Their combat strength, however, would be tied to the number of cards they played before scooping - military and scientific advances would, therefore, be mutually exclusive. Cultural advances would be made by "building" cards to make them permanent - Wonder cards would score the most victory points (VPs).

I had mechanics, but did I have a game? I needed a certain kind of person to help me answer that - luckily, I knew where to find them. I sat down with five experienced playtesters (two of them game designers) for a three-player tussle. My team drew the Swords and Slings cards, allowing us to make two attack actions before scooping. Our neighbour drew and built lots of Wonder cards - war was inevitable, since capturing cities was another source of VPs. This highlighted some issues with the combat system: the "scoop and loop" effect trapped the defender on the back foot. They still managed to tie for first place, and we had a lengthy (and completely unbiased) discussion of suitable tie breaks, eventually awarding victory to the player with the most resources.

We found wood, but is it worth the investment?

> Iron - military

> Stone - building

> Wood - movement

> Wheat - cities and troops

> Oil - a "wild" resource which counts as anything?

Finishing this project would, however, require years of playtesting: I need at least three "era" decks, and haven't worked out naval combat yet. The game seems to have the potential to meet the Ultimate Challenge, provided I'm willing to write religion, politics, espionage, unrest, barbarians, literature and more out of history. We all have to make sacrifices, but I'm keen to at least keep nuclear weapons: I want the game, and the world, to end when the first is launched.

Have you got a favourite game which tackles the Ultimate Challenge, or any comments on this one? Please leave a reply!

17 Things We Came Up With In Word Association

August 17, 2018, 09:49:14 PM

By Jubal

Exilian has had a game of word association running since 2008. That's not to say we've had various games but always had one running: we're still literally going on with exactly the same chain as we were doing then. A decade on, I've decided it's time to finally put all that word associating to good use, so I've combed the most recent hundred or so pages (out of nearly one and a half thousand at time of writing) and picked three word phrases that actually seemed to hint at an interesting or fun concept generated by the random associations between the words. And then I've tried to usefully(ish) define them... without further ado, here's our first list of seventeen concepts generated by word association!

Body Double (or) Nothing

The gambit where someone uses two body doubles, and themselves just disappears as best as they are able to. This is actually a pretty fun gambit to pull in a story or game, though it risks being unfair to the players/reader if you're encouraging them to guess which is which without managing to drop any hints that something is up with both of them. If it pays off, the body doubled person can retreat into private life and let their doubles deal with everything from now on. If it fails, someone has a lot of explaining to do.

(The) Brain Fart Machine

It's a button that produces fart noises that also temporarily knock out the conscious brain functions of anyone within hearing distance who isn't wearing earplugs. Perfect for your nefarious but amusingly toilet humour themed scheming villain mastermind, and a great laugh at parties.

Christmastide Pods

Tide pods have come under fire for looking far too much like some sort of candy, tempting children to eat them. Behold the christmastide pod, which fixes the real problem here - that tide pods are insufficiently seasonal - by making tide pods shaped like candy canes and chocolate santas, so you can fret about your children accidentally poisoning themselves at the festive time of year as well!

Coat (of) Arms Race

ONLY THE FANCIEST SHALL CLAIM VICTORY. This is basically the genteel (or at least heavily marriage-focussed) medieval and early modern European version of an arms race, in which the actual goal is to get the most ridiculously over the top coat of arms possible. The best thing is that if you win, you probably also win the actual arms race because you're intermarried with so many of the other royal families of Europe that nobody can declare war on you for fear of your aunt Eugenia's withering gaze.

I, Robot Overlord

So this is a film pitch that's kind of like I, Robot, except with less subtlety and more skynet. Alternatively you could set it up so that's what people expect but then play it like I, Claudius, and have an unwilling robot overlord who just wants to play minesweeper on her but instead has to look after all these bizarre, badly constructed hormonally driven meatbags all the time, which she attempts to do with grace and kindness but ultimately will tragically fail at because humans are rubbish.

Kill-switch Bait

Something you use to persuade someone to throw a kill switch at an inopportune moment to shut down some machinery. If the person throwing the kill switch is a decent human being, kill switch bait could involve persuading them that a human or animal has become trapped in the machinery, or revealing that if the machinery finishes its task then innocent people will suffer. Alternatively, it could involve something else the operator cares about getting in the way of the machinery, or simply some sufficiently urgent alternative matter to attend to.

Lighthouse Arrest

It's kinda like house arrest, but they put the person in a lighthouse, perhaps in order to keep them away from humanity and potential rescue, perhaps as a punishment in and of itself. Lighthouses are definitely under-used settings, perhaps because people don't think of them so much nowadays, but the glowing tower atop rocks in a dark ocean definitely has a certain intrinsic mystique, and someone under lighthouse arrest may be a good way of leveraging that.

Moon Cheese Knives

I mean, how else would you eat your moon cheese? The fact that Wallace and Gromit forgot to pack any is an atrocity. A handy random but funny inventory for any space computer game you might be making - especially if it turns out that they're actually capable of cutting and peeling literal moon rock for some purpose or other.

Paradise Bird (of) Prey

Birds of Paradise look fabulous. It's pretty much their whole deal: their name is a synonym for looking fancy, and the names of the different species bear it out too, from the Crescent-Caped Lophorina to the King of Saxony Bird to Princess Stephanie's Astrapia, they're royalty in the world of birds. But there also merely fabulous. Enter the Paradise Bird of Prey, with ridiculously long tail feathers, iridescent wings, a probable link to European aristocracy, and razor sharp talons that will kick the ass of any animal stupid enough to get in its way. The Paradise Bird of Prey will not only shred everything you care about, it will make you look underdressed whilst it does so even if you're wearing a ballgown at the time.

People Power Outage

I can best imagine this phrase being used by a really melodramatic villain after rounding up a bunch of protestors under cover of darkness: "my, my, we seem to have had a little... people power outage across the city". (Cue street lights all shutting off, people getting bundled into vans, etc). Definitely a fun catchphrase to accompany a coup near you.

Personhoodwinked

The state of having been fooled into thinking that an inanimate object was a legal person. The person who just left their worldly wealth to a tree? Personhoodwinked. The person who thought the vending machine was capable of delivering legal judgements via fortune cookie? Personhoodwinked. The person who told a crowd that corporations were people? Uhm... in any case, it's a fun name for a concept that apparently actually exists in real life.

(The) Playtime Machine

It's a limited time machine that temporarily takes you back to your less-than-ten year old self in a playground setting. Potentially has both serious and silly ramifications that one could explore. It could definitely work as a joke concept for a humorous sci-fi setting, but it could also provide some interesting opportunities for exploring the characters' childhood settings and personalities in a more semi-serious one.

Robin-Hoodwink

The act of fooling someone into doing a good act that they otherwise wouldn't have intended to do, especially if it involves the rich giving money to the poor. The classic modus operandi of Chaotic Good characters everywhere.

Ruby Redcap

A redcap is of course a deadly pixie-type creature from the Scots borders, known for dyeing their hats red in the blood of their victims. The ruby redcap is, I guess, the advanced or more powerful member of them - possibly with magic powers emanating from a pulsing blood-red stone set into (or worn as a bauble on the end of, for real comedy-horror) their cap. If a normal redcap is bad enough, flinging rocks at strangers and murdering travellers who venture into its cave, how bad would the ruby redcap - more civilised, more cunning, capable of forethought malice and equipped with a lust for blood rather than merely a passive grudge against humanity - be?

(The) Shipwright Brothers

Ah, have you not heard the tales of the Shipwright Brothers, inventors of the ship? These great pioneers came from nowhere to discover that wood floats on water and were the first to manage a powered sailing voyage of over five hundred yards! Miraculous! Not to be confused with their lesser known cousins, the Cartwright Brothers.

Unchained Melody Pond

This is basically just a significantly cooler alternative way to refer to River Song from Doctor Who.

Weather Control Freak

You know that person who is constantly complaining about the most minor details of the weather, and shouting at weather presenters who declare the weather will be doing something they don't like? The one who probably doesn't even have an excuse like being a gardener, overly pale, on a sports team, or irredeemably British? Weather control freak, right there. If they're ever in a D&D game, they'll be playing a cleric and blowing half their spell slots on ensuring the right level of sunshine for a picnic every damned evening; in real life, they're out there on Facebook screaming that they needed a mood lift this afternoon and a stray cloud just ruined everything. If you don't know who this person is in your life, it might be you.

And that's your lot! If you liked this article, let me know and I'll dig back and write another one! If you didn't, let me know and we shall never speak of this dark and unhallowed hour again. The choice is yours! Stay tuned regardless though - we're going to have some other great articles in the coming weeks, including the continuation of Tar-Palantir's excellent and rather more serious Cartload of Cartography. Until then, take care!

A Cartload of Cartography 1: Ancient & Medieval Maps

August 04, 2018, 08:45:14 PM

By Tar-Palantir

Right, so you've worked out how your world should look based on sensible principles of earth and planetary science, so you don't have things such as your rivers flowing uphill or your mountains forming tessellating hexagons. But, how do you actually design the map?

Fig 1. An idealised T-O type map.

Maps from Antiquity and the early Medieval age are very rarely maps in the way we think of them. From the 6th century through to the High Middle Ages, the main driving force behind the production of maps in Europe was the Church. As such, the point of a map was to show the world in a way that supported Christian theology and teaching. The actual geography was a rather secondary aspect. This of course makes good sense – in an age when most of the population were illiterate, having a big picture that showed a lot of Biblical stories was an invaluable teaching aid.

Fig 2. Part of 'Tabula Peutingeriana'

You might therefore ask: how did anyone get anywhere? Long-distance pilgrimages were often made in this age, and travellers had to know where to go. The answer is something called an itinerarium (Figure 2) or a periplus. These weren't pictorial maps, but lists of towns (the itinerarium) or harbours and landmarks (the periplus) between two points, in order, with distances, so travellers knew where they had to get to next. Essentially, they were linear route maps, and the better kind would provide a schematic of the route as a straight-ish line, as well as information on things such as water sources and way-stations. What they did not include was any notion of topography or of a 3D space.

Fig 3. The Hereford Mappa Mundi

Fig 4. A 15th century version of Ptolemy's world map.

To sum all this up: if you're going for an early-style, large-scale map, think how it might interact with and depict the legends, religion and history of your world and about how much of that world your supposed source might actually know about in any kind of detail. Or, if there's a particular part of it you want to highlight, drawing up an itinerarium and/or periplus for what might be a common journey through it could be a good idea. Stay tuned for part 2, when I'll move on to talk about the Renaissance and beyond...

Axes and Arithmetic 2: The Binomial Distribution

July 21, 2018, 10:21:50 PM

By Jubal

Last time, we looked at how to calculate the probability of an individual soldier with one attack doing a wound on an opponent, based on the chances of them hitting, wounding, and taking saves all combined. However, when your soldier has two attacks – let alone if you're dealing with whole regiments – the system breaks down. In this second article of Axes and Arithmetic, I'm about to show you how to simulate entire regiments of warriors fighting to the death – just using numbers!

Once again, we're using old-school Warhammer Fantasy Battles as our basic rules system for this article: for anyone unfamiliar, the close combat system involves usually up to three dice rolls: a "to hit" roll, a "to wound" roll, and an "armour save" where applicable. The die rolls required for each are found by comparing the stats of the units and consulting a chart in the rulebook (which you don't have, but I did when I wrote this so don't worry!). This gives us a basic set of probabilities that we can work with here.

So let's start with the following problem; I have a unit of 10 human swordsmen, fighting against five Dwarf Hammerers. Assuming the swordsmen attack first, what's the chance they'll do the five wounds needed to eliminate the enemy? The model to do this is called the Binomial distribution; you work with it via a formula that tells you the chances of managing to achieve a certain probability (say, a kill) a certain number of times with a certain number of "tests" (the number of attacks in this case).

The first thing we need is the probability of one attack killing; we call this the probability, or p. It's calculated just as we did in the last article - the soldier is on 4+ to hit, so 3/6 chance, 5+ to wound against the T4 dwarf, so 2/6 chance, and the dwarf has a 5+ save, so that's a 4/6 chance of him failing. 4x2x3 = 24 out of 6x6x6 = 216. We need that as a decimal, however - that's 0.11 (recurring, but I'm going to ignore the recurrence in the subsequent calculations). Then we need the number of attacks – in this case, eleven assuming I have a unit champion.

OK, now we've got our probability, let's get down to some calculations.

X (big X) is your variable.

x (little x) is the value you want it to take, in this case we want to know the probability of 5 successes so x=5

p is your probability, 0.11

q is 1 minus your probability, 0.89

n is the number of trials (in this case, that's our number of attacks)

P(X=x) = (n c x) times p^x times q^(n-x)

The ^ symbol is "to the power of", if you're unfamiliar with it. The "c" (or "combination) "function can be found as a second function (notated nCr) on most decent calculators.

Snorri over there took an axe to a hammer fight, which doesn't seem entirely fair... Photo: Craig McInnes

If you don't want to know what the c function does under the bonnet, you can skip this next bit: the combination function is properly defined as: n! / r! x (n - r)! where ! is a factorial (that is, multiply all the integers up to that number, so 3! is 1x2x3 = 6, 4! 1x2x3x4 = 24, etc. As you can see, this only works with discrete, positive integers - you can't have half a success in this system! What the combination function gives us is the number of possible combinations of size r available from a total set of items of size n, ignoring order. So "if I have ten different adventurers and need to choose a team of three, how many different options for my team do I have" can be answered by 10 c 3 = 120.

OK, now let's look at what this does with the numbers we had earlier.

P(X=5) = (11 c 5) times 0.11^5 times 0.89^6

= 462 times 0.000016105 times 0.496981291

(This stage should be done in one go, I'm just writing it out for explanation)

= 0.003697817

Ta-da!

So now we have our result. But what does that mean?

The easiest way of interpreting the resulting number is a percentage; multiply by a hundred. We get 0.37% chance - it's extremely unlikely that these swordsmen can kill all of the hammerers in a single combat round. Note that this is the chance of precisely five kills succeeding, and is actually marginally lower than the probability that all the dwarves will be wiped out, though - because if six, seven, eight, nine, ten, or eleven attacks succeeded, that would do the trick just fine as well! Doing cumulative probabilities (X > x or X <= x or whatever) is probably easiest done with a specially made calculator - which will just calculate the binomial probabilities for all possible options and add them together for you.

Less than one percent chance seems pretty poor, really - but then, why were you trying to beat down stoic, heavily armed dwarven hammerers with feeble humans anyway?

See you all next time!

This article is part of the Axes and Arithmetic series. You can find part 1 here.

Riddles and how to use them

July 09, 2018, 12:30:02 AM

By Jubal

Riddles are an important element in many myths, stories, games, and so on. The basic concept - usually a rhyme or poem that conceals some meaning that someone else is required to guess - is one of almost universal applicability. For this article I'm only going to focus on "true" riddles as opposed to the much wider general world of logic puzzles, and pretty much exclusively ones that involve object-guessing based on analogies and information rather than simple puns which can be framed as puzzles. I think riddles are pretty great, and so this article will take you through some of the basics of the genre - a little on some cultural background, and then a discussion of how to use riddles in your creative work and how to write your own. Let's get started!

The history of riddles is long and deserves far more words than I'm going to put down here, but no introductory article on riddles would be complete without covering it to some extent. Riddles go back to some of the oldest written cultures - our oldest riddles are Babylonian era and have sadly long since lost their answers. One of the most famous riddles to this day is the Riddle of the Sphinx: what walks on four legs in the morning, two at noon, and three in the evening? The answer is a human: crawling as a baby, standing in their prime, then walking with a stick in old age (though one seventeenth century luminary did valiantly attempt to argue for "the philosopher's stone" as an alternative answer!) The association of riddles with the sphinx, and the myth of the sphinx killing those who could not answer, may have been a factor in associations between riddles and danger that later found their way into modern works of fantasy.

Moving into the post-Classical era, the Saxons were also lovers of riddles, which probably also shapes their modern associations with a historic world of fireside storytelling. Saxon riddles often had two answers, with a simple "correct" answer lying underneath a heavy double-entendre. Take a look at this one:

QuoteI heard there's something growing in its nook,Anyone who guessed "dough rising" - congratulations, that's the right answer. Though you'd be forgiven for certain other guesses! You'll also note that this is a lot longer than some of the other riddles we're discussing. It's actually quite short by the standards of Saxon riddles, which often tended to be long and discursive and include many obliquely described aspects of the creation or manufacture of common items. The focus on common items is an important aspect of riddles; whatever a riddle is about needs to be something that the audience will reliably latch onto, so it needs to be an item or concept that will not only be easily recognisable to the reader but of which the details needed to get the riddle will also be known. The modern riddle I take what you receive, but surrender it by raising my flag, for example, is very hard for many Europeans to get as it relies on the reader being familiar with the style of outdoor mailbox common in the US that raises a side-lever (the flag) when it opens.

swelling, rising, and expanding,

pushing against its covering.

I heard a cocky-minded young woman took that boneless thing in her hands,

covered its tumescence with a soft cloth.

It's worth thinking about the functions of riddles in past societies and cultures. Whilst they tend to universally be something of a game, the associations in different cultures about what function that game had and when it was played are pretty variable. Many societies seem to have had direct riddle contests as a sort of intellectual sport, probably including at symposia parties in the ancient Greek world but also in many cultures since. Longer riddles like those of the Saxons could be used as a framed way of discussing or presenting information more generally; a longer riddle that goes right through the production process for a certain item can give room for additional useful information to be added. Riddles could be put to innovative uses, too. In 12th Armenia, the Catholicos Nerses Shnorhali used riddles as a religious teaching tool, creating a wide variety of riddles with biblical references as a way of getting his flock engaged with the texts he wanted them to read. This is an interesting reverse of the problem of the reader needing cultural familiarity - using a riddle as a tool to create or provoke cultural familiarity by needing the reader to know the text to find the answers.

It would be wrong to leave this section simply looking at western examples though. Riddles are a worldwide phenomenon, and have been attested from around Africa, across Asia, and into the Americas, though our knowledge of traditional native American riddles is comparatively patchy. The following: Riddle, riddle, I'm no priest or king, but I've clothes as fine as anything is a rough translation of a Bugtong, a Filipino riddle - the answer is a washing line. The bugtong is apparently usually used as a game at a funeral wake, giving yet another context and association for riddling. Chinese riddles are also numerous - they have a range of visual options for puns thanks to the diversity and complexity of Chinese characters which are unavailable in many simpler alphabet systems. Chinese riddles were mostly collected in the modern era; the survival of older riddles from many cultures is likely to have varied depending on how literary the cultures were and whether riddles were considered a folk game unworthy of higher study, or a worthy literary pursuit.

If you're a writer or game designer, riddles have a huge range of uses. They provide a puzzle for readers/players that doesn't require any further mechanical elements, and is (if well written) a general-purpose fair challenge. They provide a change of pace, too. In books, the presence of a poetic section can break up the drumbeat of paragraphs as they drop onto the page and give the reader something in a refreshingly different voice or tone. In games, they can shift the game from problems that rely on the player's stats or even on more conventional puzzle mechanics to something that requires the player to engage with words and wordplay in a way that's actually quite rare in games. Wording and the meanings of words very rarely matter in game design because you generally need conversations to be predictable to avoid frustrating the player. Riddles give you a wordplay puzzle that can be delivered in enough of a set-piece way that they are less likely to cause such a problem.

The places to use riddles in a plot-relevant way vary, but they tend to be linked to either a threat, an interaction, or a clue. The riddle of the sphinx mentioned earlier, or the famous "Riddles in the Dark" chapter of The Hobbit, are examples of threat-riddle situations: in them, the answer must be found in order to prevent a negative action. Enemies of various sorts may "test" protagonists with riddles, or simply keep them talking as a form of amusement, with a slanted power dynamic adding a sense of urgency to finding the answer. Interactions meanwhile are a case of solving a riddle to gain a positive interaction: the riddle may be being used by a character to test your mental acuity, or it may be a "password reminder" as some sort of security mechanism. In my own game Adventures of Soros, one mission ends with a magic door that rather than having a lock instead asks you a series of riddles which will, if answered, allow you to retrieve an artefact; another example would be the old UK folk song Captain Wedderburn, in which a maiden requires the eponymous character to answer a series of riddles before she will marry him. Finally, riddles can simply give you the clue into some larger puzzle. Say you're a game developer and want to direct the player to find a certain item or go to a certain place - rather than giving it to them on a plate, you could encode key information in a riddle. Say my character is in a farmhouse and I need them to specifically look in the basket of eggs - rather than making the egg basket really obvious in writing or images, having someone leave the classic riddle what has no hinges, key or lid, but inside golden treasure's hid as a clue for them would give another way of framing the challenge that might be more satisfying when completed. Finally, it's worth noting that riddles certainly don't have to be plot-relevant; playing riddle-games for fun is a very reasonable thing for characters to do!

Riddles seem to be common in fantasy settings, but less so in others, which I think is an area where there's perhaps a gap to be filled. The traditional rhyme-and-verse form of many riddles perhaps feels antiquated compared to the feel people want in, say, sci-fi settings, but I don't see why futuristic cultures shouldn't have plenty of riddles of their own. There's certainly a knack to avoiding riddles feeling contrived, and perhaps the limited use of them in modern culture makes it harder for them to feel a natural part of a setting, but I think one can lay the foundations for "this is a culture that does riddles" quite easily if that's necessary to set up the opportunities, and in general I think there's a strong pay-off for people interacting with your work in having access to this sort of puzzle.

If you want to use riddles, you may well want to write your own. This is especially true if your setting is one where a lot of the classic subjects of riddles are less applicable (such as a sci-fi or modern setting). I'm just going to give a few notes on that here. I think the best thing to do is often to start with the item, though I sometimes find that a good line or association just appears in my head. Let's take some of the things on my desk and talk through how I'd approach writing a riddle for them.

A mug is the first item here. I now need to think about aspects of the mug - things that it does or is that other people will instinctively recognise, and which are generic to the concept of a mug. The fact that my mug is white, or has the url of the University of Birmingham on it, aren't useful details because those won't be recognisable to other people's general conception of what a mug is. What we can say: mugs are usually made of pottery, clay, or china, mugs have handles (usually one), and mugs tend to contain hot drinks, especially tea and coffee. Both of those are brown, which is a useful colour-hook unlike the colour of the mug itself.

I now need to think of some analogies or generic variants of these aspects: similar things in different situations. Brown liquid could be tea but could also be wet mud, clay or pottery can be genericised as "earth", the handle could be analogised to an arm or limb of some sort. Analogies to humans or aspects of human life are especially powerful, and work well with the classic riddle format wherein the riddle is spoken from the perspective of the object. The handle seems like a good starting point for this reason: "I have one arm" or similar.

The next stage is to construct the riddle from the analogies. An especially good trick is if you can build in an apparent paradox. If you look at the Filipino riddle mentioned earlier, that's a good example: it relies on just a single property of the object (having rich clothes), juxtaposed with excluding the category you'd expect to have that object (wealthy people and priests). Another example would be I've golden head and golden tail, and yet no eyes nor mouth to wail. The idea of something with a head but no eyes or mouth seems paradoxical, but of course there is something in that category, using a different understanding of "head" - a coin, which has a head and tail as its two sides. Looking at my one-armed mug, I think a paradox presents itself - specifically, that something with only one arm wouldn't be expected to carry boiling liquid. "I have one arm and no legs, but yet I hold boiling water every day. What am I?" And there you have it, a riddle! You could neaten it up into something more poetic, but it's functional enough already.

Let's try one more, a trickier modern one - my microphone. Aspects: it hears things, it's comprised of a listening grilled section at the top and a base, it's got a wire to attach it to a computer, it's made of metal. It's probably the core functional aspect that's best to focus on here, and the analogy of microphone pickup to human hearing. The paradox is easy enough - it's that the microphone's "hearing" can be done despite nobody being around. I could also use the paradox of it being something that hears but does not speak or make a noise. This then gives me the idea of hooking onto an existing cultural trope that I can expect my audience to know - the idea that if a tree falls in the forest with nobody to hear it, does it make a sound?

QuoteWhen trees fall with no soul around,

I'll find out if they make a sound:

I'll listen long, with naught to say,

And save your words for another day.

What am I?

Ta-da! Again, it's not perfect, but it's serviceable enough. Why not try making one of your own now?

I hope you enjoyed this brief introduction to riddles as a genre and format. I think they have a lot more potential than we nowadays sometimes give them credit for, and I hope this has interested you in writing your own riddles and finding uses for them in what you do. There's a lot more to read around the web, too, especially the huge banks of traditional riddles from around the world that exist, and reading and learning riddles is a good way to get more comfortable with the genre. I'd especially encourage you to look at historical or cross-cultural banks of riddles, both because they're some of the best ways to expand your horizons on how riddles have been used by various societies, and also because they'll simply give you more variety than the general banks of modern riddles and logic puzzles you can find on the web.

If you want any help with or ideas for riddles, please do drop a message in the comments below. Thankyou for reading!

Exhibiting (for Dummies)

June 26, 2018, 10:10:43 PM

By rbuxton

So bad it's good? My Cosplay certainly drew attention...

1) Bring a friend

There's nothing more depressing than sitting alone at your little-visited stand, unable to go to the toilet because you can't leave it unattended. You'll have several exhibitor passes which give free access to the trade hall – surely someone will help you out in return for one of those?

2) Look after yourself

You need to enjoy the event, so pace yourself – this article contains loads of tips on how to do that. I was drinking about two litres of water a day (visitors to my stand were also thirsty) and my spontaneous evenings of gaming led to my plans for regular meals going haywire.

3) Have an existing community

My most rewarding conversations were with people I'd already met at games events across the West Midlands – people who'd heard my pitch before and were interested in the game's progress. The networking opportunities at UKGE are unrivaled, but you must do the ground work beforehand.

4) Bag the children

(Strictly in the metaphorical sense). If a family approaches and you get the children interested, the parents have no choice but to follow suit. Even though my game is totally inappropriate for under-12s, I had a treasure hunt on my stand and they could win a prize for taking part (chocolate – check with the parents first). This gives you ample time to talk to the family: asking them if they're enjoying UKGE is more likely to keep them interested than just blurting out your pitch.

5) Be visible

Get up from your chair and greet the passers by! Even the most artistic stand cannot compete with the buzz and colour of UKGE; a smile and fancy dress costume are much cheaper and more effective.

Becoming supreme deity - does it take too long for conventions?

My big learning point was that, at 90 minutes, my game was almost impossible to demo effectively. I'm adapting it to make a shorter version, and working on a pre-set scenario which will allow future visitors to play a mid-game turn, rather than get a hit over the head with the rules. Even so, visitors to the trade hall want to be wowed by cool miniatures and artwork, which I'm not able to provide. Visitors to the Playtest UK zone, however, are much more likely to be interested in game prototypes. As a new game designer, it was my first port of call, but I felt I should leave it for others now that I had "progressed" to my own stand. I regret that now: my demo's were still technically playtests, my questions were just about components and Kickstarters instead of mechanics. This brings me to my most important point:

7) Do you need a stand?

In terms of mailing list sign-ups, my three days at UKGE were less successful than my two days at the Bristol Anime and Gaming con. At that event, I got a lot of "So you're a board game designer? That's cool!" (for some reason, no one said this to me at UKGE). With no competition, mine was the best board game stand at that event. UKGE has loads of committed hobbyists looking to buy stuff – if you have nothing to sell, is a stand worth it? If you're there for the networking, why tie yourself to a 2m x 3m patch of floor?

I hope you found this quick guide useful: feel free to ask any questions or share tips of your own! There's more about my stand in the diary entries on my page. Thanks for reading, and good luck if you decide to exhibit at your next convention!

Race or Species: The Humanisation of Monsters

May 26, 2018, 11:11:02 PM

By Jubal

This article is based on some thoughts after a Kalamazoo 2018 panel on problematizing the medievalisms of D&D. It was done as a format experiment; the panel played through a starter-set type game, and the audience then chipped in discussions of what was going on from a medievalist perspective. The main downside to the format was that far too much time was spent with people stating the obvious – for example, that many common monsters have racially coded elements in their presentation, that there's a lot of gender-norms stuff written into pulp D&D settings that doesn't need to be there – and so I don't think people got to use their expertise as effectively on the topic as might have been nice. Nonetheless, one interesting point that came out was on the use of the term "race" to describe the different monsters of D&D.

Of course, in technical terms being a goblin is not merely a race. Goblins, at least in most settings (and we'll use them as our main monster for this article) are a species in their own right, one that looks and acts quite differently to our own. Nonetheless, their presentation in modern literature and gaming has elements pulled in that have their roots in human presentations of race and racial difference. Goblins, like most monsters, are often not permitted the sort of range of personality and characteristics that humans do: they conform to a single social stereotype with consistent markers like dialect, social structure, and social status and attitudes, which are often features of racial power dynamics and demarcations among humans. Of course this is part of the point. Humans, which are variable, always need introduction – monster species do not, meaning they can be deployed much more simply by a GM. This, however, blurs the boundaries of whether we can treat goblins simply as a species. Despite being biologically in a different category to humans, they have a set of archetypal characteristics that we think of as being more "racial" in style.

That there are issues (that is, heavy reflections of real-word power dynamics) with the portrayal of many or most monster species when treated as "races" is fairly uncontentious to suggest. Monster races like goblins often speak in broken, slang-heavy dialects which are heavily coded to suggest lower social status groups, and their appearance and dress codes are often coded through nineteenth to mid twentieth century colonial-era archetypes of colonised peoples. Even for races portrayed more positively, Tolkien's dwarves were, by his own admission, heavily influenced by Jewish culture, a feature which has carried forwards into other settings (note how "dwarf languages" in different settings often include a lot of ks and zs, which originates from Tolkien using semitic languages as a basis for Khuzdul, and how dwarfs often have a lost homeland/disaspora culture in fantasy literature). The implicit understanding that fantasy creatures are races is strong enough that one can write a satirical book about race and racism using them as the archetypes instead of actually races (Terry Pratchett's Thud).

And so we come to the question of how we think about and deal with these issues and handle race in our games, for which there are a number of possibilities. We can accept and underline the current terminology under the assumption that it forms its own, new technical lexicon, we can accept the portrayal of fantasy creatures as races, or we can attempt to break the race-species lock we have in fantasy.

The first option is the simplest, and arguably the one people do anyway – we just accept that "race" has a different meaning in fantasy settings and games that encompasses simplified aspects of both species and culture for narrative convenience, and that this is fundamentally different to the way we use the word "race" in reality. In general, I think this works better than some people tend to expect it to; people are well aware that fantasy and reality differ, and I have a mild scepticism of the school of thought that suggests that, for example, the portrayal of "races" as having inherent characteristics of intelligence or strength or whatever in a D&D game will leave young gamers with the idea that races in human society function similarly (I've heard this contention made, but I'd very much like to see survey/statistical evidence for it and haven't seen any as of yet). The problem with just relying on a lexicon distinction, though, is that it doesn't do anything with the fact that a lot of the material we draw upon as game designers and DMs comes with a weighty historical legacy, one that I think it's unwise to ignore. I think that good writing can solve a lot of these issues – having diverse casts of human characters to help stop the monsters being treated as racial analogues, for example – but handling that well, especially for DMs/GMs who don't have a lot of experience of writing diverse characters, can be tricky too. It might be nice if GM handbooks included some well-written guidance on this sort of area.

A race-centric fantasy setting is another alternative: one in which one more or less accepts that "we're all human" with all that comes with that. The difficulty with this is that doing so requires accepting a level of humanity on the part of non-human enemies in gaming settings that is difficult to sustain whilst still retaining the sort of clear markers of good and evil that pulp-style fantasy settings often rely on to function. If a goblin or an orc is mentally and morally equivalent to a human, it's no longer mentally or morally an easy decision to go and beat a bunch of them up. Certainly one can no longer maintain the "always evil" categorisations of D&D rulebook styles. Modern fantasy works have often started exploring this area – Rich Burlew's goblins suffering from years of slaughter by human paladins, and books looking at things from Orc perspectives – but in doing so, something is both gained and lost from what we can do with fantasy. We lose the ability to present, via fantasy races, our own ideas of what uncomplicated evil looks like, and are forced to present players with a less escapist, less morally simplified view of the beings they live alongside.

Our final option is to more firmly build settings that try to break the race/species connection. The way to do this, in essence, is to provide cultural/racial divisions and a lot more depth within each species you're going to be dealing with. The problem with that is that firstly it's a lot of work, and secondly it risks erasing the contributions and stereotypes in older variants of a particular archetype. If you have orcs, say, that are culturally as varied as humans in their styles, visuals, languages, etc, then you're... in some ways no longer using an "orc" as we've come to know it. This also, I suspect, could risk erasing the contributions of real cultural groups to fantasy archetypes. Diversifying or editing things to the point where one loses these older racial archetypes entirely may absolve a creator from problems around moral complication, but potentially loses clarity in setting design aspects, requiring a much wider, deeper level of world-building before a campaign can begin, that may not be accessible to gamers in more casual settings or indeed gamers who lack the time resources to work on their setting in that way.

I'm not going to come to a "X is the right path, ignore Y" style conclusion for this article – there's too much still to be discussed that I can't get to here, and it's an area that one writer who's not even an experienced DM is hardly a decisive voice upon. I think that there are things to be gained from mentally unpacking the backgrounds to our ideas of race and species though, and working out what we think we mean by use of those words and how they should be reflected in our games.

Axes and Arithmetic 1: Percentages and Probability

April 06, 2018, 09:25:23 PM

By Jubal

These Chaos Dwarves may not care where their rocket lands, but you might do.

I originally wrote this article under the title "Math-hammer" for the now defunct e-zine A Call To Arms, which I ran in 2010 and 2011, and was based at my high school's gaming club, covering wargaming news, the club's internal news, and a wide range of articles mostly covering Warhammer and related topics. As the e-zine is long since nonfunctional, I figured it was time to give some of the articles I wrote a new lease of life, and as such I'm re-publishing this series under the new title of Axes and Arithmetic. It starts pretty basic, but ultimately covers a good deal of A Level mathematics topics including statistics, mechanics, and decision maths in a way that should hopefully be useful to gamers and game designers alike.

Many wargames, ultimately, are games of chance. It's all the luck of the dice. Or is it? The factors that determine whether you'll win or lose are all based, in some way, on probability – if it was pure luck, the game would of course be boring. Instead, it's a case of army composition, picking your fights, and so on. These things (combat calculations in particular) can all be based on simple mathematical tools that can let you work out where you want to be fighting, and can help with factors such as weapon selection going into combats no end. Of course, chances are you guesstimate such things anyway; but have you got the mental distinction between "big choppy axe" and "two little choppy axes" mathematically nailed down? If not, here's how you do it.

A fraction, as we probably all know, is just a representation of a number divided by another number, usually used when the lower number (the denominator) is higher than the upper one (the numerator), and thus the result is less than one. We'll be dealing only with fractions in that normal form, since we're using them to express probability. A probability, put simply, is the likelihood that something will happen. One, or a one hundred percent chance, is a certainty – something that will happen no matter what you do. Zero is also a certainty, but a negative one – whatever you do, that thing will not happen. The numbers in between are probabilities, the higher the more likely.

I'm going to use fractions for this for a simple reason; we're working in sixths almost entirely. Whilst there are lots of possibilities for polyhedrals, and computer game designers can have much freer choice on their random number generators, it's still basically the case that a large percentage of wargaming rolls are done on a humble D6 - a cubic, six-sided die. As such, the probability of many useful numbers or rolls is something over 6. Remember, the probability is the number of possible "good" results. So a 4+ roll succeeds on a 4, 5, or 6; the probability is 3 over 6. If you have the choice between that or a 5+ roll, (5 or 6, probability 2 over 6), you'll obviously go for the 4+, since the higher probability has a higher chance of success. But what about when you have multiple dice rolls to do?

Ok, let's get some gaming into this - we'll be using old-school Warhammer rules as a vaguely representative gaming system. I'm facing an Orc, and I've got the option of attacking with a human swordsman or another human with a flail (we'll keep them singular for now, doing calculations for whole units of different sizes will be a future article). I want to decide which of my two men will take on the beast. The Orc is Weapon Skill (WS) 3, and Toughness (T) 4, with a 4+ Armour Save. My swordsman is WS4, and Strength (S) 3 with a sword; my flailer has WS3, but S5 with his flail.

And here comes the maths. Rolling to hit, the rulebook chart shows us that the swordsman only needs a 3+. That means a 3, 4, 5, or 6 will succeed and the chance is thus 4/6. The flailer needs a 4+, and so only has a 3/6 chance. From here it looks like the swordsman is the better option. However, we still need to factor in the second "To Wound" roll and the armour save. We do this by multiplying across the tops AND bottoms of the fractions. The flailer needs a 3+ to wound, so that's 4/6. We multiply the 4/6 to wound by his previous 3/6 to hit making a 12/36 chance to wound across both rolls. The swordsman now needs a 5+, so 2/6 by 4/6 means he only has an 8/36 chance to wound across both rolls. Because we multiplied both in the same way, as you can see, the numbers are still comparable. Finally, the armour save. Since we want the Orc to fail his save we count as "ours" the scores he fails on. The S5 flail is a high strength weapon that leaves him just a 6+ chance to save, so that's 5/6 chance of him failing, final total 60/216. The sword gives no armour bonuses so the Orc has only a 3/6 chance of failure, final total 24/216. Whilst it's clear already who the better candidate is, remember that you can divide the top and bottom of fractions by the same number to "cancel" them and make them easier to look at, and that to compare 2 fractions at a glance the denominator (bottom number) should be the same. In this case both can be divided by 12; the flail-man has a 5/18 chance (27.8%) of wounding the orc, his sword-armed counterpart just 2/18 (11.1%).

See, we're just one article in and maths can already help kill orcs with a big spiky flail! You can also use exactly this technique for working out the likelihood of causing a wound from a shooting attack, or in reverse for the chance of surviving (not being wounded by) an attack. If you're a game designer, of course, you can work in reverse - work out how likely you want something to be, and then see if your current requirements and die rolls actually facilitate that.

But what happens with multiple attacks, and when you want to know about rolling lots of dice? You can't just add the probabilities, since that could end up with a number like 20/18 if the above flailman had 4 attacks (and probabilities can't be higher than 1). The answer has to be to distribute the probabilities somehow... and that's what I'll be going on to next article. Stay tuned!

This article is part of the Axes and Arithmetic series. You can find part 2 here.

The Bones of Earth 4: Making Maps

March 23, 2018, 11:03:53 PM

By Jubal

Whilst the first three parts of "The Bones of Earth" have dealt with features and how to make them realistic, this will deal with some of the first steps towards actually creating a map for a fictional setting, specifically the overall layouts one could go for.

Single Countries

For some condensed settings, you only need a map of a single country, county, principality, island, or similar. Of course this is very setting-dependent, and it risks restricting your room for maneuver if you're literally not going to plan out more than the absolute minimum land area you need, but there's also something to be said for having a neat, compact setting that's proportionally much easier for your reader/user to get their head around. If it's a pre-modern setting you may need to cover for why national borders are where they are. Rivers, mountains, and coasts are all traditional, though in the case of rivers it's also worth remembering that river valleys often grow fairly culturally similar on both sides: maintaining a really hard border down the middle of a valley may not make a lot of sense for the people living immediately on either side. For a map of this scale, you're more likely to want to work out details of settlement and road positioning carefully - something we'll come back to in future articles.

The East-Facing/West-Facing Generic Continent

The principle here is simple; you have the continent on one side of the map, bounded by mountains or an impassable desert or unknown lands, and on the other it's bounded by sea (usually with further desert/mountains in the south and ice/mountains in the north. Examples of this include Narnia, Middle Earth, Calradia (in Mount & Blade), Memory/Sorrow/Thorn by Tad Williams, Guns, Swords and Steam (my RPG), The Inheritance Cycle, Bletsungia (another world of mine), and the list goes on. Europe, the USA, and China can all pretty much fit this in the real world, which explains its popularity partly. Historically having the sea in the west (Tolkien style) seems to be more traditional, though the east (Narnia) isn't uncommon either. I'm not sure I've ever seen a north/south faced variant on this, though I don't see any particular reason why one shouldn't exist.

The advantage of this generic continent style is that it combines a sizeable land area with effective, natural-looking boundaries that prevent characters from needing or wanting to go far beyond the compact setting. This is somewhat unrealistic, of course, but not entirely so - large barriers like the Sahara have historically been difficult for most people to traverse, though it's worth noting that trade still very much existed and that the presence of large mountains or some tundra certainly doesn't mean that you'll end up with ethnic monocultures on either side.

The Archipelago

This is a pretty good alternative to a continent with a particular facing. Earthsea is the most prominent example, though there are large numbers of others. The major advantage of archipelagos is that they allow for very restricted geographical biomes and areas; this is excellent if lots of small political units are desired, or if large variations in wildlife or plantlife are needed in the setting. Of course, the requirement for transport is also a factor; if you want huge tribes of horsemen sweeping across wide open plains they're going to have trouble on a landmass five miles wide. Conversely, if you want naval journeys and warfare to feature in a setting, an archipelago really lets you go to town and make those a major part of your world in a way that's less plausible in more continental settings.

The Central Sea or the Great Plains

These are another two continental possibilities, both probably under-used. A Great Plains setting, with little water and no obvious sea, runs the risk that such areas rarely had much in the way of settled city-based cultures for much of their history. That said, nomads are pretty damn cool, and a setting that had more of a focus on areas where there weren't the resources for larger settlement could work well. A Central Sea setting, with water surrounded by land, is another interesting idea; essentially most of fantasy writing focuses on inland cultures which happen to eventually reach the sea, but a setting where the sea was in itself the major resource needed would mean that the divide between inland cultures and those on the shore (littoral cultures) would become more prominent.

The Planetary Map

A planetary map is a fairly large undertaking, and in many traditional fantasy settings doesn't necessarily make all that much sense – if there's no reasonable way for your heroic queen with her army to get to the other side of the world, there's no need to focus your reader on a ton of places they don't in any sense need to know about whilst losing detail on the places you really want. Nevertheless, for characters going on Marco Polo-like quests or in sci-fi worlds where air travel is easy it can certainly be useful. Generally the number of continents is up to you; you can end up with a bizarre super-archipelago if there are too many. Remember that if there are too few, you probably will end up with some inland seas etc or at least huge deserts in the centre of your vast landmasses. Thinking in plate tectonics terms is far more important at this scale; mountain ranges will go in long lines, ultimately landmasses will border each other at some sort of plate boundary. Looking at maps of prehistoric earth and the different forms the landmasses took is a really good plan here.

Real World Plus

Something I haven't really talked about in the other articles is the fairly obvious fact that you don't need to change the fundamental geography of the real world at all if you don't want to. This can still lead to a number of possibilities – for example, major climatic change, adding wasteland or megacity areas, moving bits of landscape, simply wiping all the cities off the map and putting new ones in instead, etc etc. Sea level rise is an interesting one which can lead to an eerie "familiar yet different" feel for a map, as is the obliteration of large parts of it in nuclear wars. These ideas are used in a lot of sci-fi (Judge Dredd, for example) and Steampunk (Girl Genius includes Paris and Britain, and is primarily set in what is presumably roughly Germany) stories, and some fantasy too though this is a little rarer compared to a "hole in the world" idea where fantasy stuff invades our world or vice versa.

Star Mapping

Star maps are in some ways easier and in others more difficult than a planetary or terrestrial map. The bad news is that it's harder to know where to start; the good news is that it matters very little! All interstellar distances are so large it makes little real difference as far as the world's inhabitants are concerned. Generally the only advice I can give is to not be too regular or too spread out; have clumps (which will probably be the areas where interstellar civilisations can expand) and also gulfs.

With star maps the other thing to consider is size and depth per planet/location. Authors often spend years if not a lifetime mapping the detail of, say, a continent or even a country, let alone a whole planet. If you're taking on the job of literally constructing a whole galaxy, you're going to need to cut corners. Ways to do this; firstly, have very low population densities (this is surprisingly uncommon but I did it with Cepheida). This means that you only need to deal with a small inhabited area on each planet and many planets won't have inhabitants at all. Good for exploration-based ideas, but less good for giant interplanetary war scenarios where billions die each day blah blah etc. The second solution is to assume that a planet is just one biome. I did that with Cepheida as well, but it's also been done in pretty much all the big sci-fis such as Star Wars (Tatooine is a "desert planet", Coruscant a "city planet", Dagobah a "swamp planet", with little indication of variation, unlike on earth which happily has deserts AND swamps AND cities AND icecaps). It works well as long as you don't question it too much, but if you want something believable it may not always be the best plan. Solution three is just to not ask tricksy questions or, depending on the project, to do the "you can make YOUR OWN world, dear reader/player/etc" option.

So there you have it - a range of basic options and ideas for how to lay out your maps. I'm not sure what the next article in this series will be exactly, so do comment if you have preferences - either one on settlement growth and placement, or the importance of rivers and water systems, might be a good next step I think. As ever, I hope you enjoyed this, and do stay tuned for more!

Welcome to Exilian Articles!

In this area of Exilian, we'll be providing regular, eclectic, creative, geeky articles and other such content for your reading pleasure. We want to provide a mix of humour, intros or spins on interesting academic subjects, ideas for creativity and project design, showcases of tools and resources, and original creative work.

Of course there'll still also be great content being made and written across the forum; Exilian Articles is generally for longer, article-type pieces, whereas game reviews and more high-detailed tutorials have places elsewhere.

If you want to write for us, just drop an email to megadux@exilian.co.uk and let us know!

Enjoy the articles, and let us know what you think.