Exilian Interviews: Matthew James Jones

December 16, 2025, 04:47:25 PM

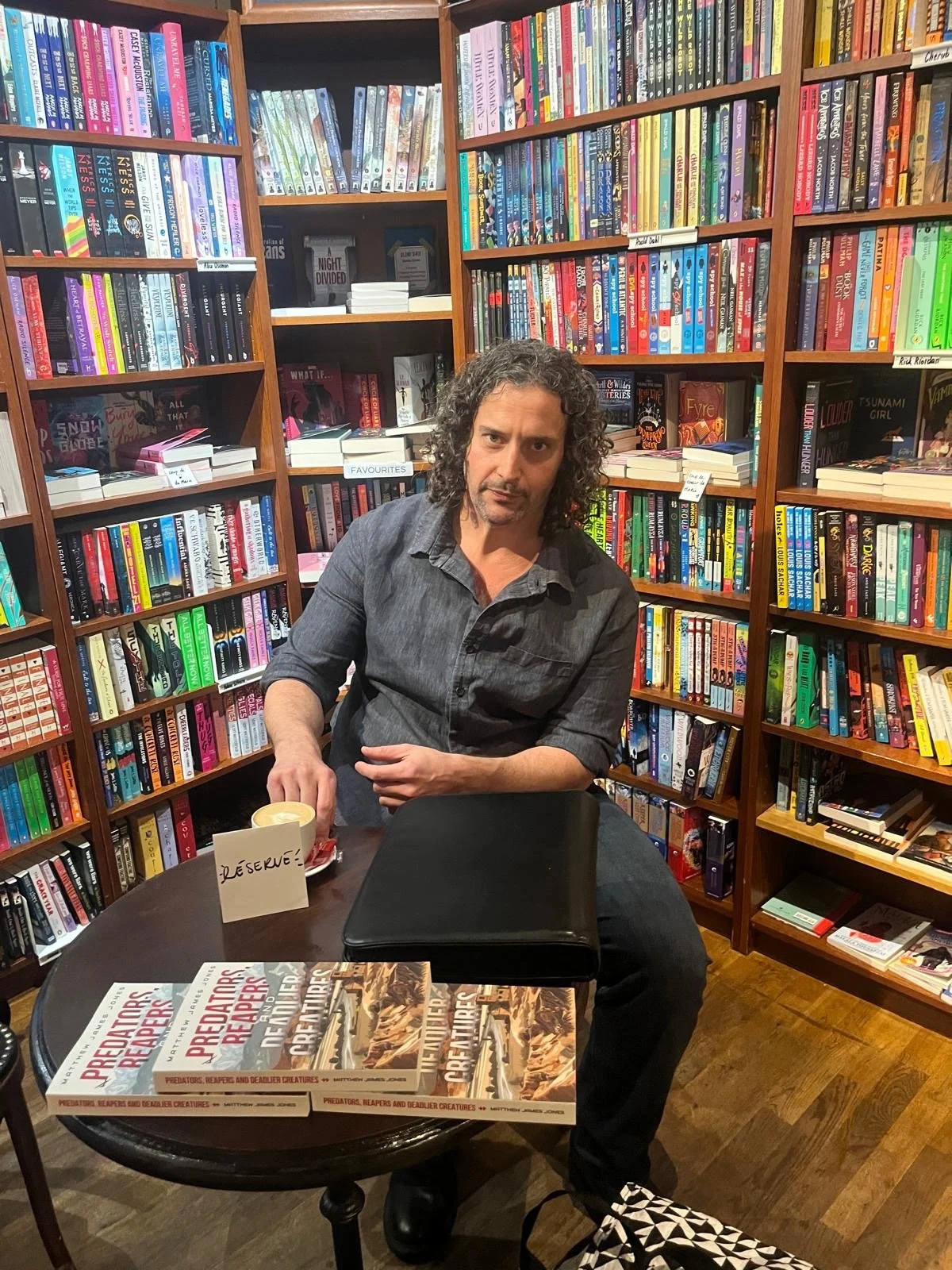

Hi all and welcome back to our irregular series of Exilian interviews! This time we've got a two-section piece sitting down with Matthew James Jones – poet, war veteran, and author of Predators, Reapers, and Deadlier Creatures, a visceral fantasy-realism view of the war in Afghanistan – starting with a review by Jubal and then a Q&A with the author.

Predators, Reapers, and Deadlier Creatures is a hell of a book, which I mean in at least two of the possible ways you can read that phrase. It's a book that you shouldn't steel yourself before reading, because there isn't any plausible amount of steel that can withstand a book that at times drops its turns on you with a written force borrowed from one of its titular drone strikes. You should read it when you're in the right place to read it, nonetheless: it's probably the book I've read this year that will stick hardest in the back of my mind, in a way that's a testament both to the writing and to how psychologically tricky the subject matter is.

To give the synopsis: this is a fantasy book about the war in Afghanistan, told from the perspective of a drone pilot - an experience that the author, Matthew James Jones, is writing from directly. The base Jones' fictional self lives on has a mix of real, fantastical, and luridly somewhere-between issues: but this is not a puzzle, or a setup for adventure, or even really a horror story. It doesn't want to comfort you with the structure of a genre tale: it is a story about the stories that people tell to make thin veneers between themselves and the hands they place on a computer keyboard in front of them, and a story about the breakdown of the stories we tell ourselves about who we are or ought to be.

To give the synopsis another way: this is a vivid walkthrough of someone's PTSD. Its core subject matter is the mental dissonance of war. Whilst I've never been to war, my brain locked onto enough of it that it hit me hard in the resonances.

To give the synopsis a third way: there are wars, and people hurt people and love and die and things smell and blood is sticky on your hands even if you never touched it directly, and some people out there are still desperate for good toilet roll. There's also a sasquatch. It doesn't go well for the sasquatch, either.

So to say I enjoyed, or loved, this work would feel almost wrong given how bleak its subject matter is: instead I was compelled by it. The book placed me at the next remove from the book's drone operators who watch humans being blown to bits on a screen: watching weirdly coldly as the characters, there in my little wood pulp entertainment medium with its ink words twitching along like supply trucks, took themselves onto the next page and then the next. My brain often wanted to turn it into a tale: one of those things where things will be resolved with, if not a victory, then a lesson, or a bittersweet hope. The testament to the book's power is that it held me in a space with none of those things, with no lock or key, and yet I could not leave it.

The thing with the way the book is written is not that that it's a book that is unrelentingly doom-laden, or depressing: people die, people joke, people live, in a suspension of doom, a veneer that is so fragile as to be transparent, and yet is clung to like some latter-day mental aegis. Nor, though, is it inherently hopeful: survival is not a victory, it is just survival. If there is to be hope, it has to come from something you do with the survival afterwards, after the last page has been closed, and that's entirely up to you. The writing neither allows the proper anaesthetic of nihilism to dull its sense of pain, nor the balm of hope to heal it. Those are high thoughts, and our protagonist is busy sneaking food to a sasquatch, exacting petty revenge on someone who deserves it, or hoping to take a slightly more comfortable dump. Or giving orders relating to blowing very real, human people to bloodstained pieces. That piece of comedically jarring dissonance is orchestrated throughout the book in continual, discordant flurries of notes and motion, giving you little chance to settle your mind and attempt something so futile as wrapping your head around what that situation might do to a brain.

I cried on page seventy-three: but that partly says something about the efforts my mind was taking to not fall into the midst of a book situation that I, unlike the title character and the author, to be frank probably would have ended up in worse shape from. It also says something about my particular feelings regarding owlbears. Given a character I have written a lot of and hold very close to my own heart as a writer is a gentle, curious, childish owlbear in particular, the impact of seeing a character likened to one amidst the pressures and terrors of drone warfare had an impact on me that was visceral enough that it's many weeks since I read that page and it's still sitting with me.

Another brutal cleverness in Jones' writing is in ripping the bandage off. Not ripping the bandage off to show the reader the sanitisation of war – we modern readers have known those lines rehearsed for a hundred years by now – but instead in ripping the bandage off the dehumanisation of its villains. As humans, we want the lines to be drawn well between our good guys and our bad guys, between our normal and abnormal: and when those lines are crossed by fictional villains, they are crossed in ways that are tempting, where we are shown the danger of using the ends to justify the means or the fantasy of doing a bad thing for justice or some other good cause. In Jones' book, he has people doing genuinely disgusting things, and then pushes you, face first, into the fact that those people are human, not as a cautionary tale, not as a setup for some grand revelation, just that people are out there, getting twisted up by the world, their minds not so many logic points away from your own. The horror is not the fear of being that person, but simply that you can understand them, simply that evil is human and that the horror becomes banal. The carpet is rolled up, what was swept under it lies bare, and oftentimes there will be nobody with the will or power or both to stop it.

And yet, the book did not leave me wallowing in depression either. There's sometimes a certain deathly pompous grandiosity to depressive feelings incited by books, and it can be easy for stories so rooted in the horror of war to disappear into a vast moral gulf lurking in the heart of a soul. This is not a book like that: it's a book of people who cope. It's often very funny, with side-boxes providing laconic humour or perspectives from other characters and with a very heavy sense of physicality throughout – there's a sense almost of slapstick at times, until it's again and again revealed that the theatre of war is not hosting a performance and the violations of the characters' humanity were real all along. The characters live around their absurdities, their pattered jargons and human quirks, and they duck behind them as cover only momentarily before the next day comes, and then the day after it. It eventually breaks most of them, in different ways, but coping can often, if not always, be done by a broken person: it's not a high bar to set, it's just a bar you get on with clearing.

I think I'll be processing this book for a long time to come – not until I've finished doing so, because I don't think I will, but until I come better to peace with the fact that I can't. What Matthew Jones has written is a spanner in the engines of a mind, an unprocessable, honest, painful fantasy that refuses to be dislodged, finessed, or rounded off.

There's a power in being stopped like that, caught in mental flight and brought tumbling to vivid, colourful, murderous, stinking and irrepressibly human earth: and this book has exactly that power.

Who knows? One day, a force like that might even stop a drone.

The Interview

Matt: Absolutely. Concern about the dehumanization of drone war is one of the major motors of the book. When I first got back from Afghanistan, I developed online training for junior officers on the ethics of drone war, still obligatory. About the necessity to say no to an unlawful order. About how, when you "strike" a villager, you lose the whole village. About generals who ordered the strike then refused to watch the mothers collect what remained of their sons in baskets.

Simple enough to find drone-porn on YouTube if one is so inclined. Perhaps you can even catch the banter of the drone operators, bloated with racial slurs and pre-judgement, rationalizing an unjust strike against a wedding convoy. Pause – the groom waves a white veil frantically as a flag of peace, his parents slaughtered.

Trigger warning? Who said that? Stop trying to stuff the world in a bottle – get better at feelings.

Y'all need to know how easy killing has gotten. Now they're delegating the hard parts to AI, like a kid who doesn't want to write his papers. But it was language they killed first, with their sanitized combat chat, which cancers through my novel, growing in strength, until human beings open their mouths, and the war speaks.

Jubal: Besides wanting to process your own experiences, what brought you to write this book in this particular way? Was it an instinctive approach for you, or did you do a lot of planning out how you were going to approach it?

Matt: Oh, my dude – don't get it twisted. Years of polishing my mask and cape have allowed me to appear like a fun, spontaneous person – this is a carefully cultivated illusion. Beneath the constant flow of crass jokes that I call charm, I'm mostly cyborg. One who leaks radiator fluid and calls it tears.

Which is my way of saying that "Predators, Reapers and Deadlier Creatures" began as a spreadsheet, a systematic breakdown of scenes/character/foreshadowing/point of view, but then the characters came to life and burnt the script. There's six or seven moving threads here that comprise the sweater: love story; detective story; war story; mythic story; ghost story; and so forth. I wrote it for everyone.

The expository boxes emerged naturally, rendered as flash fiction. Because the civilians in my writing group got so swamped by the foreignness of the warzone, they stumbled over the jargon and slipped into the poo pond. After I got the grant from the Canadian Council for the Arts, I could afford to throw cheddar at the best editors I knew. So the text was folded and refolded, katana-steel.

Jubal: Did you have any pushback to the fantasy parts of the book? Did anyone think it was wrong in some way to add those fictitious elements into a recent, real war?

Matt: At one point, Random House was seriously considering the text, and they said, "Not so sure we can sell the Bigfoot – can you write this more like 'The Yellow Birds?'" For those who haven't read it, that's a pretty straightforward war/PTSD story, not so much play in form. I was more inspired by the time travelling in Slaughterhouse V. There is, actually, a precedent for fantasy and war stories blurring. Catch 22 does it well, frenetic. Those who've been to war understand how reality-bending it is, how surreal. How the mind crafts little escapes.

Q: A student, forced to buy the book: "Is the sasquatch real?"

A: Matt, in his crusty prof costume: "You know I made up all the characters, right? That characters in stories are just word-puppets?"

Wise editors understood: without the Sasquatch, it's a grisly drone story, painstakingly wrought, a too-tall glass of pain. Pretty sure you're gonna ask me later about hope, because everybody does, and part of that answer is here. Hope is a function of the imagination; I kept my book pure, and weird, because I believed in it.

We can call it artistic integrity, or we can call it stupidity, but only time will tell if I'm playing the long game well, or dying in obscurity.

Jubal: It's hard to explain "Predators, Reapers and Deadlier Creatures" to people without the term 'magical realism' – which it isn't in the strict sense, in that there's a particular post-colonial element to that genre. Still, there's a similar sense of fantasy as psychological fracture under the pressures of a system here. Was magical realism a genre you were explicitly drawing on?

Matt: Afghanistan was a particularly bizarre moment for post-colonialism. We knocked the Taliban out of power in the first year, launching their guerilla endurance campaign. But my book takes place in year ten, when coalition forces had spent a decade building roads and infrastructure, propping up the world's most corrupt government under Karzai, training the army and police. The rhetoric was: if we leave now, the Taliban will take back control, so we stayed.

Until we left. Now the Taliban are back whipping women's feet in the marketplace.

The rhetoric was also: we fight for women, which was pure self-delusion, comforting.

So for twenty years confused soldiers found themselves drawn into an unwanted act of post-colonial nation-building. We needed shovels, not rifles. You can't build with a Reaper, just destroy. In our rich-world hubris, we imposed democracy on a tribal society with a different background and values. So they bled us, and we bled them.

I think writers do turn to magic when they aren't allowed to tell the truth. I was always inspired by Salman Rushdie, his anti-colonialism, anti-fanaticism – the way he not only wrote stories, but lived them. Toni Morrison's "Beloved" comes to mind: the ghost arrives, beyond metaphor, to embody the haunting of ancestral wounds, unchained.

The world is boring, and broken, and unfair; writers use magic to topple structures of power to inspire people to make change. I can't actually throttle billionaires no matter how my fingers twitch. But watch, in text, how I can drag a Musk through word-tar, then douse him in feathers.

Magic is inherently democratic, James. No one can claim to own it; we are only fleeting conduits.

Jubal: Your book is written in the first person, where you as the author are also the narrating character, quite explicitly – but there's also that gap, or at least that sense of fantasy, where the story departs from "lived experience". I can't think of many other authors who've done that, except possibly Dante. How did that sense of the relationship between you and you develop, and was the book like that throughout drafting?

Matt: Fortunately, I have the world's most banal name. Maybe John Smith competes. As a writer, the common name has been a bane – making me hard to find and follow. Sure, I could have chosen a nom de plume but then I started paying for a website (www.matthewjamesjones.com) and the ship had sailed. So began my quest to redeem the name, or at least find its use.

Indeed, it isn't my name at all. It's everyone's name, the everyman. The question becomes: how can I play with the invisibility it offers? A whole legion of Joneses, marching in step with our identical uniforms? JONES emblazoned proudly on our chests?

At one point Jones says something to the Sasquatch like, "Use my uniform – the name will help you hide." Later, Jones is confronted by the Taser Rapist, wearing Jones's stolen uniform, and the security of his (our) common name: "Now we are brothers, look." The name Jones is also incorporated into one of the narrator's grief-poems, rhyming with drones, how on theme! So in these and other ways I integrated the name into the story itself.

Let's cut the armadillo. Books are always about the writer; characters are just shadows pulled from the unconscious, forced to dance. What seems like innovation here is just honesty, a unique flavour among illusions.

Jubal: Poetry is clearly important to you, both as the book protagonist and outside it. Do you find processing things through poetry functionally different, or used for different kinds of emotions, than you use for prose, or are they quite interchangeable systems for you?

Matt: Writing has been a lifeline through all of Dante's hells – but it's no substitute for therapy and professional help. Fortunately, my treatment was sponsored by the state. The problem with being a professional maze-maker is falling into your own traps. Substituting the realworld for an artificial reality where you're already king – no need to get your hands dirty with gritwork. For every writer and poet I've met who is well adjusted and hardworking, there are ten neurotic bastards out there, foaming at the mouth and snarling for scraps.

When I teach creative writing (either at universities in Paris, or through my monthly writing workshop) therapy emerges – it's not propaganda. Just a little sleight of hand where we pretend we're talking about your character's neurosis, how they got all tangled up from their childhood wounds, how they were ignored all the time as a kid so now they gotta shout at the top of their lungs – people aren't that complicated. Just wound-machines acting out our programming. So if you truly deepdive into writing character, you might just figure out your own armadillo by accident.

In terms of prose, call me unfaithful. The idea was always: start with poetry, and become a master of the line. Move to short stories and learn to rock a paragraph. Upgrade to novels and your unit of measurement becomes the chapter. It was always one path, no matter the divergence.

And now, post-book, I'm tinkering with even more diverse media, with all the enthusiasm of a soldier, post-deployment, splashing into Tinder. Somehow I find myself teaching Digital Narratives at a video-game school. Learning basic code and how to create choose-your-own-adventure stories that can run in a simple browser window, or on your phone.

It's not actually a question of medium; it's a question of audience. What are the migratory patterns of owlbears? Do they hibernate in the winter, or huddle penguin-like? Can they fly, or does the ground pull at them the same as us, capping their aerial forays to the summit of a fearsome jump? And where do I meet the bears like me, feathered?

Jubal: To move on a bit to the fantasy parts of it – you build up quite a lot of mythos of the sasquatches in particular. It would have been easier to write that character as an hallucinatory entity, but you're careful to make him embodied, physical to the narrative, existing with his own reality. Did you have any particular process or inspirations for how not only that character but also his surrounding culture came together?

Matt: I see this as a question of restraints. The sasquatch, with his limited education and vocabulary, can't waffle and riff, or fall into pits of reverie or cynicism like a Jones. It's always gotta be singsongy. It's always gotta be from the body. I wanted my most unreal nonreal character to be the most real: with pain, hunger, history, fleas.

Also catering to historic pairings like Don Quixote and Sancho, where one is rooted in a tower of the mind, and the other rutting in the stables, or dreaming of the next bottle of wine. Or, if you prefer, Asterix and Obelix. My French students at the Parisian Military Academy loved when I destroyed their favourite childhood heroes through the critic's lens. Asterix is only strong when he drinks the magic potion. Obelix, on the other hand, is a human juggernaut. On a whim, he destroys armies, sinks armadas, gets armadillofaced. The external world represents no threat to them: only a runaway Obelix can tank the story, so it becomes the fate of long-suffering Asterix to moderate his giant friend, and that's the struggle.

I tell my students that trying to live as pure intellectuals is like trying to win the marathon hopping on one foot. Alas, our bodies are stuck in these putrefying meatsacks, housing our emotional apparatus. That's why I started the Log Gym, which began with hoisting logs in the forest, just a few PTSD-riddled veterans, and expanded into a larger group of friends.

Let me point to the larger concerns of the body in the book (the strong body; the weak body; the beautiful body; the ugly body; the male body; the female body; the whole body; the dismembered body) like ripples in a pond, spreading.

Most important: those mythic sections, all about the Sasquatch gods and heroes, were hella fun to write. Somehow that mythic Sasquatch voice became one of the most powerful and important voices in the story. It's a voice that embodies home, and things lost. It's the voice of a humiliated god, forced to gnaw frogs in a bug-infested crawlspace. Voice of a lost wisdom, discarded traditions. Excavate the layers of the pyramid of suffering until you locate the base – the natural world.

Jubal: I have to ask about the owlbear (which I think you only mention in description). Was that a creature you particularly had a history with? Was there something particular to you about picking it over other beasts for that specific analogy and scene?

Matt: I always thought, once I'd shaken off the war trauma and the other stories bursting out of me, I'd write high fantasy: even ran a blog for a while, on my website, and the last post was "on imagination" featuring a furious owlbear, enhanced by moon-magic, and defending her chick-cubs.

So perhaps I have a strong association with the owlbear as a fierce protective mother, in the way of bears. Naturally a bear is not a monster, just an overgrown kitten. But fuse the bear with the long-seeing owl; throw in some brightly hued feathers, and now you have a proper force.

It was the Major, I think. The one whose "loneliness monster" was an owl-headed bear, shrieking behind a canary-cage. Because the more a creature loves its freedom, the tighter we cage it. And because the Major dreamed of being a mother, just not the kind of mother we might expect.

Like I said before, we told ourselves the war was to free women, but that was just a feel-good lie. Yet the Major fights for women, truly.

Jubal: There's a lot that's important and a lot that's darkly funny, but not a lot that's in any sense hopeful in "Predators, Reapers, and Deadlier Creatures," and indeed it might be jarring if there was – it feels more about remembrance and acknowledging, in its own way, what happened to the soldiers and victims of war. But how do you see the relationship between this and what does keep you going – what gives you hope?

Matt: Call it a tragicomedy, if it helps. Perhaps the book doesn't seem hopeful because the war was such a profound waste. But the love was real, that scene with the monsoon – "I felt one once." There was even a spark of love in that hellhole; did you see it? And true camaraderie, even among opposites, and the incongruous gentleness of one monster cleaning another's wounds.

Let's continue our theme of honesty – I am a veteran who served and saw terrible things. I got a big ol' list of friends who aren't around anymore, who fed themselves bullets. And still I poured myself into this book, both the light and the shadow, hoping I could catalyse a change. That I could push the rudder of culture the tiniest fraction of a millimetre, and get humans to think about drone war in a new way. Move culture first, then policy wonks implement protocols to curb the abuses of this still-emerging weapon.

I left home; I moved to France, descending into the writers' bohemia, to live a life of craft and words. And I hoped that people would read my work, not because I was famous, but because the writing was worthy.

There is always a hope-question and it always makes me feel misunderstood. In terms of hope, I'm the village idiot, staring at the cloudless sky with open mouth, wishing for a drop of rain.

Jubal: Finally, where can people get the book, and where can they find out more about your work?

Matt: Thanks for reading, James, and for caring enough to line up this Q&A. The best way to get a copy of the text is to find it on Amazon. Bezos is a vampire but it all started with an efficient book-distribution system.

To stay in touch, get news, and receive my sweet sweet freebies, join the mailing list. That's where I'll share my upcoming "choose-your-own-adventure" digital narrative, "Matt's Guide for Collapsed Men" which will take us to the pit and back. That one is free, pure clickbait, a reader magnet.

December's mailing-list spam, "The Fart that Ruined Christmas," is outrageous, written from the body. But what's that? You're a crackhead for images? Then Instagram's the best choice.

All owlbears welcome. All sasquatches and gnomes and gnolls and trolls and pangolins. I swing the doors open; follow my trail of breadcrumbs, all you creatures, and feast.

An Unexpected Bestiary: The Fifth Parchment

August 24, 2025, 10:40:48 PM

It's some years since I last shared an entry in the Unexpected Bestiary series, but here we are at long last with seven more strange but real creatures, with information about them and ideas for how you could use them in writing, RPGs, and any other storytelling or game design you might be doing. If you find this piece interesting and inspiring or have any alternative ideas and comments, please do comment and let me know, and hopefully there'll be less of a gap until I get to writing part six!

You can also read other parts in this series: parchments one, two, three, and four, and the Pangolin special. And with that, let's meet the first of our new arrivals, the worryingly named...

Hellbender

Photo by Evan Grimes: via Wikimedia commons.

The creature itself is rather less frightening than one might be led to imagine from the nomenclature: they're large salamanders from the eastern United States, growing up to 70cm in length and living largely in creeks in Appalachia. Their blotchy red-brown colour might have given rise to the association with devilry: their lifestyle of hiding around rocks and eating small fish and crayfish is probably rather less hell-fuelled.

Another interesting feature is that – again, despite their name – the hellbender is a good indication for water purity. After adults undergo their final metamorphosis, they have rather limited gill function and need fast-moving, oxygenated, clean water in order to be able to obtain enough oxygen to be healthy. They live in a mostly solitary way and defend particularly good spots for their lifestyle, making exceptions for mating where a female will visit a male's patch, lay some eggs which he will fertilise externally, and then leave: the males defend and raise the eggs and hatchlings for seven or eight months.

The combination of the name and habitat suggests some interesting possibilities for using the hellbender in fictional contexts. One could imagine these outcasts and refugees of hell actually being good indicators for e.g. holy water, being desperate to bathe in the purest substances possible to avoid the sight of their erstwhile fiendish predators. They'd make interesting pets and companions for tieflings for much the same reason. If given a bit more sapience and scaled up a bit, they might be more cognisant of the whole situation, living an almost monastic live in their solitary fresh-water hermitages and contemplating how the world might have been otherwise.

Ant-lion

Antlion photo by Scott Robinson. Via Wikimedia commons.

The classic ant-lion strategy is to dig a shallow pit, usually in very loose soil or sand and in a dry location, and sit just under the surface: when prey such as a hapless ant wanders above the pit, the creature pounces, using its huge jaws to grab the insect and drag it under the sand to eat it. They rapidly inject their prey with both venom and digestive enzymes, sealing its fate and causing it to start being digested before it even enters the ant-lion's body. The biggest difficulty for the ant-lion is not knowing how long it will have to wait, and they are certainly adapted to long periods without food, to the point where ant-lion larvae literally lack the facilities to poop: nothing is left unstored.

The typical thing to do with an ant-lion in fiction would just be to scale it up to make it a threat to characters. Whilst not mobile like the sand-worms of Arrakis, the similar principle of having areas of a sandy desert where huge beasts, torpid for years until something disturbs them, lurk and wait to kill below the surface would be an excellent monster for that kind of environment. You could also use the original creature in other ways, though: given their sandy hiding-holes, ant-lions are difficult and perhaps delicate to find, so if there was some need for them they could represent a particular challenge for characters whose knowledge of the land needs testing.

Cormorant

Cormorant on a branch: author's own photo.

Whilst they're not birds many modern city-dwellers think about a great deal, cormorants are still common and do have a long association with humans. Their fishing prowess has been utilised across Eurasia for both sport and hunting: they can be trained to wear a neck ring that stops them fully swallowing larger fish, causing them to then return the fish to their trainer. These days, the practice is particularly associated with eastern Asia where cormorant fishing is still done for food, but sport-fishing with cormorants was described in the west in the early seventeenth century by the traveller George Sandys.

There's no shortage of cormorant folklore and associations from around the world. They appear as far back as Homer – Hermes is likened to one in the Odyssey, and scholars have suggested that their presence in the cypress trees of Circe's island might give them an association with death. In early modern England, they were symbols of brooding, voracious greed, perhaps due to the way they tend to very visibly swallow fish whole and perhaps due to their black-clad perches looking down on the world – Milton has the devil sit like a cormorant on the Tree of Life. Even more atmospherically, Francis Meres wrote that "As great fishes devoure the small: so couetous cormorants eate vp the poore" and Shakespeare in Love's Labours Lost speaks of the "cormorant devouring time". There are more positive connotations available too, though – some have likened the cormorant's outstretched wing-drying pose (which you can see here) to a Christian cross and associated the cormorant with self-sacrifice.

As potential inclusions in fiction, they're fascinating and have no shortage of potential. There are really two angles on this: the physical cormorant, engaged in real life, and the cormorant as metaphor. If you go down the former route, cormorant fishing is a lively inclusion for any imagined world, and a real part of cultures both past and present. As companion to a more fishing village based ranger character, or a core part of life for local folk taking their boats out onto the deep river, the cormorant could add a very distinctive flavour to a world. Cormorants are often somewhat colonial, too, so e.g. "turn at the tree where the cormorants sit" might be a valid landmark in any more water-bound world.

Then there's the metaphorical cormorant: the cross-bound symbol of sacrifice, or the mysterious watcher of greed and death. The open-winged cormorant does make an excellent heraldic symbol, and the association with fishing might help link to ideas of the water and the sea, but also of recruiting and building connections (as with the Christian disciples' concept of "fishers of men"). On the darker side, the idea of the cormorant as the symbol of death and the all-consuming makes a really interesting from difference to giving that role to, say, the raven or the wolf. I love the idea of the time-eating cormorant – not chasing and snapping at it, like one might imagine a wolf doing, just waiting and watching, perched above the very cosmos on a tree both alive and dead, for the moment at the end of everything when it can gulp the very fabric of existence into its belly and fly up into the cypress trees from which none return.

Mexican Mole Lizard

Photo by caudatejake, via Wikimedia Commons.

One particularly grim urban legend about the mole lizards is that they attack people who are taking a dump, burrow inside them and shred them from the inside. Whilst this is an extremely specific method of attack for any creature, real or fictional, there's definitely a gross comedic horror to the idea of the animal that sees any brown stuff to burrow through as just another goal.

For using the Mole Lizards in fiction, there are various options. They're probably a bit too weird (and frankly, their faces are too cute) to be a good giant-scaled terror monster, but they could be good "this place is weird" creatures: just seeing one ambling through an underground environment or having someone use them to help dig tunnels or even send underground messages could be interesting possibilities. The toilet attack vector myth could work in a certain sort of comedy horror – it's something you can see being whispered among settlers in Fallout – so that's a possibility, and could be exacerbated if someone had trained or engineered them for greater aggression.

Treeshrew illustration by Joseph Wolf. Public domain.

The pen-tailed treeshrew, besides its distinctive quill-pen styled tail, has a very particular claim to fame. Specifically, it is possibly the most alcohol-fuelled creature in all creation. They drink the nectar from Bertam palms, which has one of the highest concentrations of alcohol in a natural food (similar to beer): given the amount they drink, they should be drunk about every three days on average, something that you'd expect to cause significant problems for their survivability.

However, that doesn't seem to happen, and getting hammered doesn't seem to have been selected against for this species. It's possible that the pen-tailed treeshrew has different ways to metabolise and use alcohol that humans don't – but what benefits the treeshrews derive from their lifestyle are entirely unclear.

There are a few interesting narrative options for the treeshrew. I sort of like the idea of them as the guiding mythic animal of – given the quill-pen look and alcohol combination – drunken poets, maybe bringing bardic luck or providing guidance gently swaying their way through unfamiliar landscapes or dreams. You can also of course just further hype up the alcohol tolerance and have the amusement of a small shrew drinking everyone under the table. Their environment is also notably interesting: natural rather than brewed alcohol sources, which you might find if you can follow treeshrews to their party trees, could have their uses for adventurers seeking the stuff for amusement or indeed medicinal purposes.

Hoatzin

Opisthocomus hoazin, image by Murray Foubister. via Wikimedia Commons.

One of the most interesting things about the hoatzin is that it seems to have managed to genetically re-trigger some features of ancient prehistoric bird species (a process known as atavism) – in particular, wing-claws, something seen on very early birds like archaeopteryx. For a while it was thought that the hoatzin might even be a close surviving relative of these early birds, but now it's known that they're well within modern bird categories and must have manage to re-trigger the genetic pathway towards claw usage. Wing-claws are mostly a feature of the baby hoatzin, allowing them to climb around the tree-tops before they can fly: adults often flap noisily around a nest site to distract predators while the babies clamber away, or even just drop down into the mangrove water, where they can also swim fine and then climb back up the trunk.

The bird's diet gives it a number of other issues – it mostly eats plant leaves, and has an unusually huge pre-stomach area, known as the crop, that helps digest all the plant fibre, as well as a lot of specialised gut bacteria for breaking down tough leaves. Its crop is, however, so large that it reduces space for chest muscles, which are generally quite important to birds on the grounds that they're what powers the wings. Not only that, but having a ton of digesting and decomposing plant matter passing through a lot of specialised gut bacteria all the time produces a number of other by-products – not least methane gas – which the hoatzin also needs to get rid of somehow. It does so by burping, frequently. Its diet makes it smell and taste absolutely foul, to the point where locals might take the eggs but almost never hunt an adult hoatzin except in dire need.

The hoatzin is a good reminder that as well as the animals that are useful to humans, there are always animals that people stay away from or don't use for what might seem to be their obvious purpose: hoatzin wouldn't be hard to hunt, but also wouldn't reward the effort. This deeply strange creature somehow managed to trade away a chunk of its flight capability and regain prehistoric characteristics in exchange for a life of show, noise, foul-smelling leaf digestion and constant burping: all that makes it an iconically visible part of its landscape and soundscape, but in a way that is primarily for scene-setting more than inviting human interaction.

That said, there's a lot that could be done by getting creative with interactions featuring the hoatzin. In general, for fantasy creature design, birds with wing-claws are definitely something that has all sorts of potential. Besides the possibility of using them for attack or defence, there's something weird, and thus interesting, about the idea of a bird climbing with claws, undermining the expectation of it flying. I think there might also be an interesting possibility for thinking about how hoatzin might be useful in fictional, folkloric, or even science-fictional terms: one could imagine trying to persuade someone that your area wasn't worth conquering by feeding them a meal of hoatzin as an example of how good the local food can be, or having someone try to actively collect the methane it burps (useful for lighter-than-air ballooning, though also highly flammable – a tempting target for some Amazonian balloonist gnomes).

Zokors

Zokor in the Altay mountains. Avustfel, via Wikimedia Commons.

They usually live up to half a metre under the surface, but can have 100 metre long tunnel networks, coming up to the surface to feed and then returning to their burrows. That's about twice as deep as a mole's tunnel network, but still only half as deep as a rabbit warren goes. The zokor burrows can occasionally go far deeper, up to nearly two and a half metres, but this is rare.

Because zokors are herbivores and undermine the roots of plants, they've often been seen as an agricultural pest in parts of China, and studies suggested that they decreased the biomass production compared to zokor-free regions. This led to an extermination campaign which did not have the intended consequences: meadows started having a loss of other species knocking on through the ecosystem, because whilst the zokors had been suppressing the quantity of biomass, they were also aerating the soil, changing which plants could grow healthily: their burrows also helped water move into the soil structure, which significantly reduced soil erosion problems. The zokor has generally been reclassified from a pest to an 'ecosystem engineer' – a category that also includes things like beavers, where their physical restructuring of the landscape helps support other parts of the environment.

Zokors appearing in fiction could have a range of functions – one of the primary ones being what friend of the site James Holloway calls the "not in Kansas anymore". If rather than having moles and rabbits, you have zokors digging up the crops, you have immediately taken your reader, player, etc into a space that is not conforming to standard fantasy Europe and its expected biosphere. This opens up some other possibilities: if one made the zokors bigger or the other characters smaller, one could for example even enter a zokor's burrow system. Because of that sense of the zokor being different, this would avoid players having the sort of Redwall-fuelled expectations of "oh we're in a rabbit burrow", allowing for a different sort of tone to be brought into a similar kind of scenario.

There's also, I think, something to be done with the idea of the zokor as an animal that engineers the world around it usefully. One could imagine the Central Asian steppe equivalent of hobbits or gnomes deciding to actively reorient the landscape or tend the steppes using a good understanding of how they support the meadows and high plateau grasslands. Might well-trained zokors even be used to tactically undermine an opponent's crops or even buildings en masse while keeping your own soil properly stable?

And that's everything for part five! Do let me know what you thought, especially if you do find uses for any of these creatures in your creative work (or to tackle obscure pub quiz questions) - and I'll see you all again when I finally write part six...

La Feria de las Flores

May 27, 2025, 09:24:56 PM

It was dark by the time my bus arrived in Medellín. My first impression was of lights twinkling on either side of the road, lights which reached higher and higher up the hillsides as we approached our destination. We were soon driving through what felt like an upturned bowl of stars, the mountain peaks out of sight. Little did I know that, beyond those mountains, hundreds of boxes of flowers were being packed and distributed. I did know, however, that the Feria de las Flores (Festival of the Flowers), Colombia's largest festival, was just a few days away. It was hard to miss it: every television in every city was inviting people to Medellín with a series of catchy adverts. The city's reputation, however, once centred on something very different: for two decades it was the seat of that most absolute of monarchs, Pablo Escobar.

I'm going to start with an apology: considering this is an article about a flower festival it's not particularly visual. For security I mostly kept my camera locked away, and the festival was a bit crowded for good photography anyway. I've discussed this with my editor, Jubal, and we've agreed to put the following video in as an introduction, and there's another one to watch at the end.

After a hot and cockroach-ey night at a bus station hotel I made my way south to the suburb of El Poblado. The mid-morning sun was warm and the streets a quiet, leafy green. The traffic noise was swiftly replaced by birdsong, including that of two squabbling parrots. An avocado salesman rumbled his cart from door to door and cried "Aguacate!" at intervals. I buzzed my way into my hostel and was met by the receptionist Claudia, who invited me to add my rucksack to the growing heap behind the desk. Claudia would become a fixture of my mornings in Medellín, keeping the backpackers in check accompanied by her little son and big dog. My bed was not yet ready so I joined some other backpackers for a cup of tea. I, at least, was drinking tea; they were mostly on lager, as they had been since the previous evening.

My first priority was food, so I asked Claudia where I could buy some groceries. She recommended a supermarket up the road, but I returned empty-handed. It was the trendiest and most modern supermarket I had seen for a long time; it even had self-service checkouts. To me it was just gringo products at gringo prices, so I asked Claudia where I'd find a "real" market. Surprised, she took the map she had given me earlier and added in a little circle on the very edge of the tourist area: Minorista Market. It was an easy bus ride away and I enjoyed trawling the dozens of stalls with the locals (Medellín is much more diverse than its rival, the capital Bogotá). Colombia is home to a huge variety of fruit; earlier in my trip I had encountered a fruit bowl as part of a tour and found myself unable to name any of the contents. It got me thinking that, when it comes to tropical fruit, we in the UK are limited to what can be easily refrigerated and transported. In the Minorista Market I was able to buy a variety of beautifully fresh produce. I also picked up some arepas, a kind of maize flatbread, but had to ask Claudia's help in cooking them.

It was time to start exploring. Medellín (population 2.5 million) is a long, thin city built along a river of the same name. It has a modern (but sometimes crowded) metro system which also hugs the river for much of its length. I rode it north to the Plaza Botero, home to the Rafael Uribe Uribe Palace of Culture. This imposing black and white cathedral-like building was designed by the Belgian architect Agustín Goovaerts in the 1920s, but not completed until 1982. The building's dome is off-centre as though it was intended to be twice as long; the story goes that the architect fell out with the local government during construction. Also in the plaza are sculptures by Colombia's most revered artist, Fernando Botero. Botero is widely known for making things "fat", and this is initially apparent in the human and animal figures on display in the plaza. I was told, however, that the exaggeration of certain body parts was actually Botero's ploy to draw attention to each sculpture's true focus: the bits he left in normal proportions. I'm not sure if, in image-conscious Colombia, this would have been much comfort to the models who sat for him. Its effectiveness, however, was evidenced in some of the paintings in the adjoining Museo de Antioquia. A painting of Christ, for example, shows him wearing the crown of thorns and bleeding where it has cut him. Thanks to the size of the head in comparison to the face, the blood seems to go on and on forever. It's as if Botero has given every human sin its own drop. His most famous painting, however, is of the 1993 killing of Pablo Escobar in Medellín, and you can see it by following the link below. For what it's worth, I was not personally taken with Botero and preferred the more varied and subtle style of his contemporary, Luis Alberto Acuna.

On the far side of the city centre the metro links up with a cable car network, which climbs the steep slopes on either side of the valley. It boasts some impressive murals at its stations. My journey up towards the Arví Park took me above zig-zagging streets of square brick houses. This, I realised, was what a regenerated favela, or shanty town, looks like. After ascending about 800 meters the route abruptly levelled off. All around was a beautiful and varied Andean forest. The cable car dipped and rose approximately level with the treetops; the overall sensation was one of flying (enhanced by the fact that I was the only passenger by this point). My ride ended at a very smart visitor centre, but I felt I was a bit pushed for time to actually venture into the park.

I was lucky to have a guide to Medellín in the form of John, a digital nomad from the USA. John, like many others, had made the city a semi-permanent home and knew all the good hostels and shared workspace facilities. For his work the city was perfect: modern, well outfitted with WiFi, cheap, diverse, interesting and with great weather (its nickname is the "City of Eternal Spring"). John knew when the rowdy football games were on and where the underground salsa bars were hidden. His speciality, however, was taking groups from the hostel to Carrera 70, the main party street of the city and the festival. It was lined with bars which spilled out in a mess of balloons and silletas, wooden frames holding great round signs made entirely of flowers (we'll return to them later). A stage was set up at the end of the street showcasing everything from punk music to Argentine tango.

I had promised myself a bit of a break from intensive backpacking while in Medellín. My two week stay was unstructured and I barely wrote in my diary. I chilled out, went to the concert hall and took part in a chain writing project here on Exilian. Most of my time, however, was spent at the Table. I have capitalised it here as it was a uniquely accommodating social space - for those who were confident with spoken English, at least (I was, once again, one of the weaker Spanish speakers). The atmosphere of the hostel was neatly summed up by a German friend of mine:

"Oh yes," he said, "As soon as I saw this was a 'party hostel' I knew there would be a lot of British people here."

I buried my head in my hands and hoped that the conversation would not turn to Brexit. We returned, instead, to one of our favourite topics: which of the Colombian lagers was most like urine (after a few days at the Table they all tasted equally bad). Another favourite topic was cocaine, which in Medellín flows in rivers. It was common, in the mornings, to see hung-over backpackers attempting to sell on their left-overs to avoid them "going to waste" ahead of an upcoming flight (Claudia took a dim view of this).

One night we all left the Table together and piled into taxis. We got held up at a roadblock where some police officers half-heartedly checked our passports (they did not discover that several of us had, sensibly, left them locked in the hostel). We then drove on to a popular night club, which had several busy rooms with DJs playing different versions of reggaeton music. I made many more backpacker friends in the club's large garden. There was a problem, however: everyone was very tall. This, combined with the background noise, meant that the conversation was going right over my head. Emboldened by lager and the sociable atmosphere I approached the only other short person in sight and engaged him in conversation. He was not particularly keen to chat: he turned out, in fact, to be the local drug dealer.

At about 4 am I left the club in pursuit of fried chicken. The streets of El Poblado were, as I had been promised, absolutely buzzing. I had no difficulty finding a food outlet and strolled happily down the main street, where the clubs had spilled out into a huge gathering of young Colombians. A man approached me with a big wooden tray, a common sight in the city, loaded with snacks and chewing gum. I politely waved him away but, to my surprise, he kept approaching. With a big clownish grin on his face he nudged the tray right into me and pushed me to one side with it. We laughed together at the joke but, when we parted, I realised something was amiss: he had swiped the phone from my right trouser pocket. I kept walking, humiliated, and he vanished into the crowd. It was a clever trick, but not clever enough: the phone in that pocket was a decoy, an old broken thing intended as a distraction. My real phone was tucked safely in a pouch under my shirt. Listen to your parents, folks.

I was more shaken by the incident than I cared to admit. I was frustrated at my poor judgement and the loss of my decoy phone, which I had actually planned to use as a defence against mugging. I spent the morning trying to make a new one out of an old phone case, some coins and sellotape. My story spread around the hostel as the morning wore on and the residents began to sober up. It got back to the one person I was hoping to keep it from.

"Richard!" cried Claudia as I tiptoed across the lobby, "I'm sorry but that is very stupid. I told you not to walk alone at night in El Poblado!"

I looked at my feet; there was no defence. I wondered if we backpackers are like toddlers: discovering our limits by pushing against them. The part of me that wanted to test myself against El Poblado had evaporated, and I'm glad to finally get it off my chest. I made sure my next adventure was much more tame.

Along with John and several others from the hostel I booked a place on a tour of Santa Elena, the township to the East of Medellín which is the true home of the Flower Festival. I had been told that the festival traces its origins to one Santa Elena resident's decision to carry his wares to market in Medellín on his back. This was an exaggeration at best: it was common for people to make this journey on foot with their loads (which could even include sick family members) on wooden chair-like frames. These frames, known as silletas, are now used exclusively to show off the region's flowers.

Our bus left Medellín and wound its way up hairpins to the relatively flat region above the city. It was a climb of around 800 meters and the temperature dropped noticeably. Our tour guide had provided each of us with a scarf and white paisa hat, the latter named after the people of the Antioquia region. I did wonder if our guide had a sense of humour: the disc-shaped hats were hopeless in windy mountain weather. On several occasions a gust caused the group to lose them en masse and have to run around in pursuit. As for the tour itself, we stopped first at a large statue of a silletero with his load and then drove on to a farm. The last part of this journey was done on foot along a dirt track with beautiful hedgerows on either side. The colonial-style farm building had been part-converted into a museum. In its expansive kitchen we sat down for a traditional meal, which included a local speciality: hot chocolate with a lump of cheese melted in it (an unpleasant and surprisingly greasy experience). The house overlooked the flower fields, where a vast number of species, from tall sunflowers to daisy-sized numbers, were displayed together (Colombia is actually the second most biodiverse country in the world). Exploring this garden was the highlight of the tour, and you can see why in the following picture.

Most of the farm's flowers had already been picked, boxed and delivered to Santa Elena's residents. They were busy spending the precious few days before the big parade attaching the flowers to their silletas in complex and beautiful designs. The catch was that each silletero would receive just one type of flower in their box. The event would start, therefore, with some frantic trading involving the whole community. This would have been going on at about the time I rolled into Medellín by bus the previous week.

My next tour was to Medellín's Comuna Trece, which translates as District 13. This impoverished part of the city was notorious for gang violence in the 20th and early 21st centuries, but is now - bizarrely - a tourist attraction. In the past couple of decades a combination of investment and grassroots community efforts have transformed the area, succeeding where violent military assaults failed. It was a focal point of the city's cocaine trade and the associated violence (Escobar's shadow looms large here), but the streets have been regenerated and are now full of dancers and artworks.

Our guide for the afternoon was Bryan, a resident who had taught himself to speak what he called "Street English" and later turned out to be a rapper. Before leading us up the hill into his neighbourhood he asked us not to give money to any of the children who would show off their dance moves to us. Giving to adult street performers, he said, would be fine, but the children should be encouraged to stay in school. Our first few stops were at pop-up street dance shows; we were evidently expected, but this was part of the fun. As we walked further the street art became progressively bigger, louder and more colourful. Some of the works were reproduced in the many eccentric souvenir shops.

We stopped at a small museum where the horror of the gang wars was brought to life. At one point the army was sent in but failed to eradicate the gangs. In the interest of claiming a victory the government secretly made deals with some of the gang leaders, so a false peace was created for a few months. As the buildings of the area became more and more damaged the street artists set to work claiming the wreckage as their own in protest. Most harrowing of all, however, was Bryan's own story of a gunfight from his childhood. He and his brother were watching from their window when a combatant backed right up their house to shelter by the wall. Seeing the boys looking out of the window, he told them to move for their own safety. They did so but, when they looked again, the man was dead.

Much of the investment in Comuna Trece has been spent on infrastructure: metro lines, a cable car and a series of public escalators traversing the steep slopes. At the top of the hill is a - relatively - big road on concrete stilts, and it was here that the tour ended. We had ice cream and enjoyed the sunset views over the city. I had time to follow the road away from the crowds to where things were quieter. Strangely quiet. Looking back along the road I could see what an engineering marvel it was and, from the footprint of the stilts, how many homes must have been demolished to make way for it. Just as I was reflecting on the ongoing costs of regeneration I abruptly reached the end of the road. It was unfinished, which explained the lack of traffic. A tall metal fence separated it from an older, dustier track. I peeked through and saw rubbish spilling out of abandoned brick buildings. A chicken strode defiantly across the road.

Some of my friends at the hostel were heading to a party called "Gringo Mike's Big Gringo Tuesday". I turned it down as I had more important plans for the morning: a visit to the Botanical Gardens. (I was later vindicated in my decision when an Australian friend described the evening as "Just a big gringo f**kfest, to be honest".) I arrived at the ticket office early in the morning but had still failed to beat the queue. The gardens themselves were interesting but they were not what I'd come to see. They put on a special festival of their own every year, which celebrates flowers from Colombia and beyond. These include some amazing flower sculptures, and the centrepiece this year was a wooden boat listing dangerously in a stormy sea of blue and white. I also enjoyed seeing some fat pitcher plants and the creative arrangements of tulips made by various tulip societies. It wasn't just the flowers that were beautifully decked out: many visitors had brought their highly accessorised dogs along.

The big day was nearly upon us. As a warm-up, much of the city was closed off for an enormous parade of classic cars. To my surprise this parade was led by perhaps a dozen of the city's bin lorries, polished up to perfection. Following these was a seemingly endless stream of cars, and my most vivid memory is of watching them negotiate a tricky speed bump. The next day I rose early and donned my new flowery shirt, paisa hat and garland of plastic flowers (I had acquired the latter in some nightclub or other). It was time for the cultural phenomenon which had first brought me to Medellín: the Desfile de Silleteros.

I found a good spot among the crowds lining a main road. The parade was opened by a single vintage car carrying three or four elderly people. They were dressed in white and had red scarves tied around their heads. These were some of the original silleteros who had taken part in the first parade in 1957. They were followed by a series of warm up acts: some police officers with their dogs; a terrifying armoured police vehicle (with flowers); a troupe of what I took to be Brazilian Carnaval performers. Finally the first silleteros appeared: the children who had competed in the junior category. Each carried a wooden silleta of the traditional form: a sort of stepped wooden backpack overflowing with flowers. They were chaperoned by members of the Scout Association, who kept them supplied with water and relieved them of their loads occasionally.

Next up came a lone woman, bent under the weight of her 70 Kg silleta. She carried her paisa hat in her hand because her head was busy with a strap supporting some of the weight. She had a huge grin on her face and was waving her hat to draw more and more cheering from the crowd. Every so often she span around to show off the enormous circular design on her back. It was a riot of colours and textures consisting of more flower varieties than I could possibly name. This silletera's name was María Claudia Atehortúa and she was the overall winner of the Feria de las Flores 2023.

After María came the rest of the silleteros who had competed in the emblemática category. These were the circular ones which I had grown used to and were all spectacular. There were several other categories: tradicional, which the children had been carrying; commercial in which the logos of sponsors, including Coca-Cola, were reproduced in flowers and monumental. The latter lived up to their name: wooden constructs burst out of a - usually - circular base; they were much bigger and heavier than the others. My favourite was an enormous lion's head with a mane of what looked like grasses gone to seed. The silleteros were evidently enjoying themselves, and every so often they'd put their loads down so that they could fully show them off. One man went right up to the crowd, reached in and emerged with his son in his arms; they waved to everyone together. It was a joy to watch the paraders pass by and transform from exhausted people under heavy loads to flowery, tortoise-like creatures once viewed from behind. It was a testament to both human ingenuity and human endurance. In the silleteros' six kilometre walk through the chequered streets of Medellín there was a sense of defiance, love and hope. Yet there was frailty as well: in every flower that fell from a silleta I was reminded that these beautiful artworks were temporary, and would be lost until the cycle began again for the next year's Feria.

I had time for one more adventure before leaving Medellín. I turned my nose up at the Pablo Escobar museum, which is run for profit by members of his family, and at the associated theme park and zoo. I set off instead on foot through El Pobaldo to the Museo El Castillo. This mansion was built by the architect Nel Rodríguez in the style (for some reason) of a French château. I arrived at the ornate gateway and saw a long curving driveway bordered by tall conifer trees. These, like many of the plants in the grounds, were covered in ghostly cobwebs of Spanish Moss (a sort of creeper which is neither Spanish nor moss). The whole place was reminiscent of the enchanted château in Disney's version of Beauty and the Beast. I brought my entry ticket for seventy thousand pesos: I would later learn that, back in the 1930's when the house was built, that sum would have bought me the entire property.

Inside I had a tour of the grand rooms and eclectic collection of (mostly European) oddities. My guide's use of the English language concealed a razor-sharp wit, and I'd like to share some of his descriptions with you:

"This is the only original carpet in the house which you can walk on, so please make the most of it."

"If you ask me how much the chandelier is actually worth, well I cannot tell you: my boss doesn't want me to know!"

"In this room we have a collection of seven hundred silver spoons donated to the family by a rich auntie. If you ask me why she donated them, well I can tell you: she was very rich and she had too many spoons."

I was reminded of a tour guide in Spain who had repeatedly referred to us, his audience, as his "family". A part of me had wondered if I should point out that the word isn't usually used in this context. I decided there was no need to be a killjoy and, if my new friend wanted to refer to me as family, who was I to stop him? The English language, I reasoned, belonged as much to these non-native speakers as it did to me - perhaps more so.

I was up early on the morning of my departure. The backpackers of the hostel - including, at last, some Colombians - were all fast asleep. Over breakfast at the Table I made one more friend: a French backpacker, who arrived, as many of us had, looking shell-shocked from their first metro journey. She asked me about safety in the area and my answer, unfortunately, got back to the one person I was hoping to keep it from.

"So, Richard," said Claudia during checkout, "You don't think El Poblado is safe?"

I thought for a moment. Of all the people I had met in Medellín, Claudia was the most proud of her city and how far it had come. In the backpacker community, however, my encounter with the pickpocket was by no means an isolated incident.

"I'm sorry, Claudia," I said, "But I don't."

Perhaps, had I stayed in Medellín longer, my assessment might have changed. Perhaps I could have given the Digital Nomad lifestyle a shot after all. The Highlands of Colombia, however, were calling me, and I couldn't miss my date with the world's tallest palm trees. I did not look back.

The seriousness of the history I've presented here was not lost on me during my visit to Medellín. My objective in this article was the juxtaposition of the old and the new; the violent and the beautiful; the cultural and the sex-drugs-and-rock-n-roll. I have not presented events in chronological order and there may be factual inaccuracies - please shout if you spot them. In the interest of brevity I've omitted a lot of detail: the police officers in the parade, for example, were actually on bicycles, and had their dogs sitting to attention in little doggy side-cars. It's unexpected joys like these, especially when flowering out of hardship, that make travel worthwhile. I hope this article has motivated you to put a bag on your back, go somewhere new, and see some more of this crazy, kaleidoscopic world in which we live.

Links

Here's the promised "further watching", specifically the opening, minute 6:30 and minute 10:00 of this vlog by the Mexican backpacker Alan X El Mundo:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TiSNmmEQqIg

Editor's Note: More of indiekid's travels in the Americas can be found in his piece on travels in southern Chile, and in a two-part article on the Mexican leg of his trip with part one here and part two here.

The Name of The Game

February 28, 2025, 11:31:07 AM

This is a short piece on naming games! A lot of people, especially in small gaming projects, need to find names for their game, and a lot of what some people come up with can be a little underwhelming.

Often, I think the trap people fall into is to try and take a name format they know from a larger game elsewhere, and then take something that sounds vaguely similar, without thinking about game names in terms of function. Game names, though, absolutely are a functional part of the game's marketing and experience.

Game names need to do one of three things, ideally more than one: they need to sound snappy and engaging, they need to tell people something about the game, or they need to give a hook people will be interested in. You don't need all of these in every game name - there are trade-offs - but these are core things to keep in mind.

Sounding snappy is the most subjective part of this setup, but it's important nonetheless. If game name ideally shouldn't be more than about 4-5 syllables. If it's longer, then it at least should have an obvious abbreviation. All the same techniques that work in poetry or marketing also apply to game titles: think for example about assonance (whether words have sounds that form a pattern) and alliteration (same sound/letter at the start of the words). Sometimes the best way to get a sense of this is to literally try saying the name out loud, or get someone else to do it: the instinct of whether it sounds right is easier to get in spoken format.

A brief note here on articles. "A" and "The" have quite different functions in titles. It often IS worth using one or the other. "A Tale of Doom" is better than "Tale of Doom", but is also different to "The Tale of Doom". Use "the" when you want the name to feel definite and singular, and "A" when you want the name to feel like part of something wider, more ephemeral, or more specific to a character rather than the whole world.

Telling people something about the game is a complex problem. It's a major part of game naming – you want to be informative but ideally without just saying a feature directly. So for example "Dungeons of Hinterberg" is a really good info-title. Dungeons bring the correct expectations of dungeon-crawling, and Hinterberg implies some kind of mountain settlement, and that's basically the game... but it doesn't tell you everything, and it implies some uniqueness to what it's doing, because Hinterberg is a place the player presumable doesn't know (providing a bit of a hook). It's also important that Hinterberg provides a bunch of signals that a more generic name might not – hinter makes us think hinterland, berg is a common root for mountains. Dungeons of Alzorgard is not nearly as good a name, because Alzorgard tells us nothing by comparison. Conversely, the game "Tactical Battles" is too blunt a name. Quite a lot of games have tactical battles, so why people should play your game which hasn't told them anything other than that it has a very common feature in it is left unclear.

The "hook" element can also be phrased as "does the title create a question the player will want an answer to". This is a less strongly used element, but it can be pretty effective. Usually hooks aren't phrased as questions, though there are exceptions: it's about creating a juxtaposition of things that inspire curiosity, or using something that's inherently mysterious. Something like "There's A Gun In The Office" is a hook title: it does tell you quite a bit about the game's setting (guns and offices) but primarily its job is to set up a literal Chekhov's gun effect, an expectation that the gun will eventually go off, but without being clear about under what circumstances.

There's a sting in the tail of all these parts, though, which is that a lot of them are easier, or suggest longer names, for games that are in larger, better known franchises. This is for two reasons. Firstly, if an abbreviation can apply to multiple things, you need to be a pretty big game to muscle others out. DAI, in gaming circles, is Dragon Age: Inquisition. So if you went and made De Administrando Imperio, a Byzantine management sim based on the text of the same name by the emperor Constantine VII, you absolutely wouldn't manage to get more than about five actual Byzantinists joining with you in calling that DAI rather than the Dragon Age title.

Also, bigger game names can be longer because the need to inform a player that a title is part of a series they like is valuable enough to take the extra syllables to do. The extra six syllables to add "The Legend of Zelda" to a game's title is more than worth it because for most buyers the single most important factor in their decision to buy is just "it's another Zelda game!". Conversely, if you're producing the first game in a planned series, calling it "The Apocalypse of Artodor: Swords of Awakening" doesn't work as well. You may have 10 Apocalypse of Artodor games planned, but having that in the title doesn't yet mean anything to anyone and is a lot of weight of syllables for something which doesn't have a strong pull factor. It's also notable that a lot of bigger game series start with a simpler title rather than a long one with a colon: for example, the first Zelda game is just "The Legend of Zelda".

Now, let's look at examples!

Dragon Age: Origins. OK, I know it's the first game in a series. The Dragon reference also tells me it's probably fantasy. Solid title all round.

Legend of Zelda: The Ocarina of Time. This seems a fairly long one – but most of the name is there to tell me things. First, the game tells me that it's a Legend of Zelda game, which is an already established franchise. The Ocarina of Time bit is more a hook than information, in that it makes us question "what does an Ocarina have to do with Time" and in many cases "hang on what's an Ocarina". So, informative and raises questions.

The Exile Princes. This tells me it's likely to involve rulers, maybe strategy or RPG elements, maybe exploration elements given the 'exile' element. All of which are correct.

Roadwarden. This is snappy and tells me who my character will be, really good informative title.

Wildermyth. Also snappy and tells me that a) there'll be a mythos/fantasy element and b) that there'll be some focus on the wilderness. Again, informative but the portmanteau saves on syllables, making it much cleaner than "Mythos of the Wilderness" would have been.

Rome: Total War. This tells me it's a Total War game. Even if I've not played one, Total War is a strategy concept in and of itself, so the franchise title works even if you're unfamiliar with the franchise. Also, it's about Rome. And the whole thing is done in four syllables.

Deponia. Actually one of the weaker examples here in that it tells me absolutely nothing. However, it sounds kinda cool, so fits the snappy criterion.

Under The Yoke. This is a really good one. It's short (four syllables) and it provides multiple meanings which both apply to the game. It's a game about medieval agriculture so animals will literally be yoked to plough fields, but the phrase "under the yoke" is often used for someone working excessively hard for someone else, as was the case with medieval peasants.

Tyranny. A three syllable, single word title that also gets across the overarching theme of the game, how you survive and create your own space under – while taking part in – a tyrannical overlordship.

Hopefully this illustrated some problems and possible solutions when it comes to game naming. Thinking through the three principles we had at the start – what does it tell the player, what questions does it raise, and does it sound good and do so efficiently – is a good basic framework that you can come back to.

Hope you found this useful! If you have any questions, comments, or things you think I've neglected to mention, please say so in the comments below. Or post your own game naming question/problem and I'm happy to see if I can advise at all!

The Exilian Romantasy Blurb Generator

February 15, 2025, 10:13:56 PM

Symbolic of your tale? Hit the button to find out!

By Jubal

This is not so much an article as a generator: I decided that with the advent of all the LLM slop I was actually somewhat wistful for the days of JavaScript generators - the sort of thing where you hit a button and it actually random-numbered through a bunch of possibilities that had been curated by an actual person. Is the result any better or worse than GPT? That's probably for you to decide. It's certainly less damaging to the environment.

And the topic of this generator? Well, it's been a running joke with some Exilian friends that there really are a lot of romance fantasy books with titles in the form "An X of Y and Z" these days. So many so, in fact, that one could almost... get the titles and blurbs to write themselves? As such, behold the EXILIAN ROMANTASY BLURB GENERATOR, your one stop engine for creating fantasy romance plot ideas.

Do post your favourites below and let us know if this created anything useful for you!

Without further ado, all that remains is for you to push the button and...

17 More Things We Came Up With Playing Word Association

December 31, 2024, 09:41:38 PM

By Jubal

Yes, this is what it says on the tin. We've been playing literally the same Word Association game since 2008, it has over 37,000 words in it, and the combinations we come up with sometimes create some interesting concepts that we might not have thought of otherwise. In 2018 I wrote a list of 17 Things We Came Up With In Word Association, so we're well overdue another compilation of quirky and unusual ideas created by the word-jumbles of Exilian members. Various members contributed the original posts: definitions and writeups by yours truly. Do enjoy!

1) Pub Garden (of) Eden

This pub presumably serves the Hesperidean Cider famous from Failbetter Games' Fallen London... and wouldn't it make a lot of sense if Adam and Eve were thrown out of Eden in part for drunk and disorderly behaviour? Theologians are currently discussing what the smoking rules were.

2) Stack Overflow Pipe

The most important part of any automated or human programming system is the Stack Overflow Pipe for exchange with the Grand Repository of Programming Knowledge And People Who Hate The Way You Didn't Search Enough For The Answer First. Unfortunately, attempts to redirect the stack overflow pipe into AI training have led mostly to the production of sewage-quality code.

3) Sourpuss (in) Boots

Puss in Boots is a much beloved character, but these days, audiences are surely looking for the gritty anti-hero take on the fairytale. Enter Sourpuss in Boots, an alley-cat whose best days are past him, whose boots are hob-nailed and probably have too many buckles, who wields a shiv instead of a rapier and who for some reason is still a hit with the femme felines. His adventures will include rat-slaying, dog-fighting, getting stuck up a hawthorn tree for the sake of making that trope spikier, and being a tragic dad to a tabby daughter-figure thrown out from a wealthy household and finding her way in the world. However, even if we do get Henry Cavill to do the voiceover, there will be no scene in the bath.

4) Robin Red Shift

It's like a regular robin, but it's actually green and is just always moving away from you at cosmic speeds. Probably runs on the same technology as Father Christmas' sleigh, probably not often found in gardens as you'd need a very large one to be able to see it before it left again at red-shift speed. May or may not be associated with Batman.

5) Woolly Hat-Trick

If a hat-trick is a three-goal achievement, a woolly hat-trick is a three goal achievement specifically in ice hockey. Canada, get on this one!

6) Middle Earthshot

A grand endeavour to make the world more mythic and heroic OR more hobbity in some way, maybe with an award attached. Options could include ensuring global access to strawberries, throwing blockchains into a volcano, or crying in a very manly yet gentle fashion. Weird American tech bros with Tolkien-named companies for some reason probably wouldn't like the outcomes of this prize.

7) Tone Police Force

They're out there, they're probably self appointed, and they're really mad about what you're saying on the internet especially if it's literally your own life you're talking about in your own words. Actual cops don't always get on with the Tone Police because the latter set a very unrealistic expectation for exceptionally speedy response times.

8) Forge-master-mind