Thinking Chimerically

March 18, 2023, 01:07:36 PM

What makes a chimera a chimera? Whilst of course there's the 'original model' with its goat, dragon, and lion heads and snake tail, the term has a more general usage for animals made of bits of other animals. These include the gryphon, the hippocampus, the hippogriff, the owlbear (in its post-Gygaxian/modern incarnations), the wolpertinger, the jackalope, a lot of grotesques in medieval margin images, and so on. We've even had the spectacle of a real creature being declared chimerical: the first Europeans to see platypuses assumed they were sewn together fakes, and indeed some aboriginal tales posit them as the offspring of a duck and a rakali, giving them a chimerical ancestry.

We keep coming up with and using chimeras. The gryphon may be ancient, after all, but the owlbear is only about half a century old. The inherent way that animal parts can be recombined is something we will doubtless keep playing with – but what works, and how we can put together a chimera, isn't something entirely without logic or rules. Those rules depend on what we're trying to achieve with our chimerical being, and how we feel and think about the particular animals and animal parts being used. For the time being, we'll start with a basic definition of a chimera as having the characteristics that it has parts that are recognisably from multiple animals, and that it also bears some attribute or connection to those animals.

Within that, I think there are two main purposes of a chimera: a chimera as confusion and a chimera as magnification of the animal's attributes. The chimera as confusion is exemplified by the original chimera. The purpose of the chimera is that it is wrong: it is unnatural and strange that these familiar images have been reassembled into something unfamiliar. Medieval grotesques also fall into this category, with human faces and dragon's tails and legs poking out of all sorts of places that, well, they just shouldn't be.

However, here's where things can fast get out of control, because creating something that just looks wrong is actually kind of easy: if we create a creature with sixteen limbs alternating octopus tentacles and spider legs, give it an array of eight eyes, the beak of a rooster and a big ol' fish fin, we definitely have something that is weird as hell but not really something that fulfils a chimera's function. It's just too weird, and whilst it might be horrifying, that's because of the inherent horrors of what we've created more than because the bits don't belong together. Another way of putting this is that a messy chimera can easily just become an alien, where the whole thing is weird rather than having the specific wrongness of relatively familiar elements mismatched together. Insectoid and invertebrate elements transposed into vertebrates, too, are such a staple of horror as a genre that it's (in my view probably unfortunately) relatively difficult to use them in a chimera-like situation.

So we get the twist in the chimera's tale: it relies on a weirdness that needs a certain level of familiarity to make it work. The specific horror or discomfort of the chimera is that it takes elements we know and understand, and put them in a combination or situation that breaks that image. In this sense, the especially incongruous goat head might be the most important part of a classical chimera. It's the familiarity of that image – or that of the human parts in medieval human-dragon grotesques – that combined with the multi-part nature of the creature creates the effect. Especially aspects like its multiplicity of heads manage to provide a clear mix-and-match nature and a clear wrongness while maintaining the clarity of which parts come from where rather than making a simply alien being.

They greymarne - very much not the gryphon you know and love. Author's own work.

To give a good example of just how much this works on feelings, I want to share with you a creature I've used in the past, the greymarne, a corruption of Griffinus Marinus (in much the same way that a vormorant is a shortening of Corvus marinus, the sea-crow, this is a sea-gryphon). There is very little mechanical difference between a greymarne and a gryphon – both have bird head, animal body, fly, and so on. But the greymarne has the head of a gull, and that changes everything. The gryphon is a noble steed and soars the peaks: the greymarne squawks in your face and tries to dive-bomb you. The gryphon chases wild ibex in the hills or attacks mighty elephants, while the Greymarne is out to get your lunch and will probably snack on a dead fox if one washes up in its vicinity. Because our feelings about the input animals are so different, two mechanically similar creatures come with wildly different expectation games.

Again, we have an interesting problem that parallels the one we had with our confusions, which is that some combinations that work well don't function properly as this sort of chimera, either because the respective parts don't resonate or because, to take a cooking analogy, the combination overpowers the original flavours. Enter Quetzalcoatl, stage left. The winged serpent is a fantastic image and, nominally, chimerical, including bird and serpent parts. But because most people around the world nowadays do not have terribly strong feelings about quetzals, they become a sort of adornment to the core serpent image rather than something we might think of more properly as a chimera. Generally a lot of bird + lizard combinations end up with some issues like this, giving a more dinosaur or lizardman feel than something we perceive as chimerical, perhaps due to our lower familiarity and empathy with a lot of non-mammalian creatures.

So we can move from these thoughts to a couple of core guidelines about using chimeras and, perhaps, creating new ones. There are two major ways to create a chimerical creature, either by trying to create something where the combination of parts turns the familiar into the unfamiliar, or by creating a creature where shared ideas and familiar attributes give a reinforcement to both sets of characteristics. In both of these cases, it tends to make sense to have at least one part of the animal be something that is comparatively familiar and about which the audience already has some fairly heavily embedded ideas. Mammals tend to work especially well for these purposes, because we're more familiar with them and tend to feel less like they're alien to us.

To give a couple of examples to end with: let's first make a wrong chimera. We'll start with something cute and familiar: a small cat, for example. We then need to focus on giving it some things that are incongruous, but also familiar themselves. A good idea for a secondary head might be that of a rat – we get the incongruity of "hey that has a second head" but we also play with the idea that this creature both represents predator and prey, perhaps even with the 'prey' side being the more malevolent one. Add some webbed back feet, like you might find on a duck, and we have a creature of damp ditches or sewers from a fantasy city, gnawing on foul meat and frightening the regular stray cats and dogs with its terrifying multi-headed shadow – and yet at the same time, it's all almost something you could imagine taking in, giving a bath, and letting settle down for a nap by the fire.

To make a type two chimera, we need two animals that we have similar feelings about, unlike our cat, duck, and rat. Let's once again start with a mammal, this time a badger. We think of badgers – probably not wholly correctly – as grumpy but loveable, stoic and somehow defensive, tenacious creatures. What else do we give those attributes to? Well, a tortoise or a turtle. We'll go with a more aquatic style of turtle to emphasise the difference: shell and back legs of a turtle, front legs and snout of a badger. The resulting Bortle (or Machvaku, or Tadger, or Bouldersbane, to come up with some names) is a creature of wild waterways, defending burrows it digs into the riverbanks. Slower moving than a badger on land, it moves more quickly by water, and its powerful bite and sharp claws give it a reasonable means of defence. It could easily be given some magical attributes to set it apart too, perhaps its shell having particular properties or it having some ability to sniff out particular other creatures or items that a story character might need.

So there you have it, some chimerical thinking and a couple of examples of how to apply it in your fantasy setting design and games. What did you think? Let us know below!

Goblin Week: 28 Goblin Concepts To Cause Chaos In Your Stories

January 29, 2023, 09:28:11 PM

By Jubal

Goblins are one of the commonest creatures in modern fantasy, but at the same time can be hard to use well. Since the division between Tolkien's goblins appearing in the Hobbit and then the term Orc being used for the more epic threat in the Lord of the Rings, the idea of a goblin has been increasingly pressed into evoking the chaotic, children's storybook feel of Bilbo's adventure rather than the epic nature of Frodo's. This idea of a small, almost childlike nature can pose problems with game styles where one is simply fighting them in combat encounters, and they can easily lose their sense of mischief and chaos if made into generic enemy cannon fodder.

At the same time, goblins aren't goblins if they're easy to live alongside. Whether due to confusion or malevolence, whether in funny or scary ways, goblins are here to make our lives more difficult, and to sit at best uneasily alongside humans who have jobs to do and mouths to feed and who value a lot of things, like safety, that have never really occurred to goblins.

So that was part of the challenge for these goblins - it being goblin week, the aim certainly was to celebrate goblinkind rather than simply produce malevolent cookie-cutter bearers of evil. But nonetheless it was important to produce goblins that evoke that sense of childlike mischief. The other part of the aim for goblin concepts was to think of goblins as individuals - a goblin horde nees little introduction, but giving goblins an individual existence for story characters to interact with is a different tricky challenge.

So without further ado, here are 28 goblins, four for each day of goblin week, with a few sketch illustrations by the author. Hopefully you'll find some of them interesting, useful, or simply enjoyable - do let us know if you use any in your RPGs or storytelling. And, of course - happy goblin week!

Pritskik is a goblin who values order, and to that end thinks that nothing should move its location ever. Goblins breaking things is a known problem: goblins nailing, bolting and glueing everything to everything they can find is a new challenge.

Mroblaff the goblin is a mage-priest, granted spells by gods who are very absent minded, can't spell well, and don't understand mortal life. Mroblaff's spell list includes Summon Ladybird, Somewhat Ladybird, Moss Depth Word, and Ethereal Beak.

H'thizz meanwhile hunts rabbits with the aid of a pack of stoats. H'thizz has one great rivalry in the world, with an enormous green-eyed housecat called Godfrieda. Neither has yet won.

Lubgom the goblin has one eye, a stick too big to carry, and a tendency to pick fights with angry chickens for fun. The main surprise is that Lubgom has an eye remaining.

Mujg the alehouse goblin throws salt in the beer, drains the flasks of anyone bringing their own liquor, and switches the mugs of anyone putting potions in someone else's drink. The barkeep is yet to work out why her tavern does so well.

Frottl is a goblin that steals naughty children, on the assumption that they must really be goblins who need better training. They are usually returned within ten days with strict instructions on how to vex their parents yet further.

Stiglit is the goblin who "borrowed" the third day's post in this series, both out of curiosity and to use as nest lining, which is why it only appeared on day four of Goblin Week.

Jumbrokkle is a goblin who lets deer and moles into people's gardens, because they look horribly tidy and it can't be good for anyone to have things all straight and pruned like that and Jumbrokkle has Concerns.

Dlup the goblin was a legendary hero who went around human weddings across the world, breaking their crockery because the noise sounded pretty. In some cultures breaking crockery became so expected that humans started breaking their own as a tradition. It is perhaps a pity they do not invite a goblin to enjoy doing it.

Sopipt is a very small goblin who makes little holes in feather mattresses and crawls in them to sleep or store shiny things, which has been the cause of a number of back pain problems among the local nobility.

Aaugh just likes yelling. Aaugh has gone looking for a thing called a "void", having been told that it's there for you to yell into, which sounds *perfect*.

Xherb likes rotting smells and carefully sneaks around putting single bad fruit or occasional dead voles into barrels of fresh-picked produce every harvest time, just to make sure everyone else can enjoy them too.

Peppkrik wants to be a lighthouse keeper, but lives next to a mud pond in the fens. The dancing lights of Peppkrik's home in a large bush have caused many a full boot as people head off the path at night. It has been nearly a year since the reed-bed was last set on fire which is probably good going.

Tsmits the goblin grew up without other goblins in the cave of an owlbear, and wears a feather hat and a fur coat because it's just Correct that things are supposed to have feathers at one end and fur at the other. Tsmits is almost a brilliant tracker but makes Very Excited Owl Noises slightly too often upon seeing a quarry go by.

Flimminy lives on a mountain and pretends to be a goat. The lack of difference in attitude means few goatherds ever notice.

Very Goblin Svleck lives in a goblin village in the marshes and actually *is* a small goat. The lack of difference in attitude means few goblins ever notice.

Jlamk is a goblin general in the finest traditions of generalship: wearing Many Shiny Items, making Loud Shouty Noises, and Not Getting Near Actual Scary Fighting. Jlamk is very successful at all of these. Especially the last one.

The goblin called Oorasolb has ears long enough to trail on the ground, a problem resolved by tying them up into a large pointed hat. Most goblins now assume Oorasolb is a wizard, and that any protestations otherwise are sheer modesty.

Rvaich the goblin is an artist who sculpts in mud, straw, and horse dung. Rvaich leaves very kind gifts of modern art outside the doors of less artistically inclined humans in local villages, and assumes their rapid disappearance is because they have been sold so quickly.

Metterflup is confused by humans making themselves work so much, and steals people's work tools in the hope of giving them a hint that they ought to not do so sometimes.

Klab lives in a rockpool and likes eating sand, and quietly makes sure any food people take onto the beach gets a good seasoning of it as well.

Zrand maintains a ruined temple. Humans don't appreciate how much work refurbishing wall art in nouveau mud-and-rat-bones style is. Zrand carefully piles skulls, scatters straw, and places rusted spears that shine in the moonlight, in case someone visits.

And sometimes, in the old chantry, the goblin sings.

A Juggler of Words: Making False Etymologies

December 28, 2022, 12:01:47 AM

By Jubal

Puns and plays on words are funny, but they tell us more than that about our relationship with words and ideas. People have been fascinated for many centuries with the problem of where words come from, and fun etymology facts, true or not, are a staple of social media clickbaits.

Finding these connections between words, whether true or not, can also be a source of inspiration. Ideas and concepts previously disconnected can click together and create ideas about a setting, story, or imagined past. Whether referring to things around the home, or links between animals and people, or relations between great powers, reimagining our relationships with words can be a route to reimagining how they connect together and how else we can imagine the things themselves. These new connections might generate ideas for creatures, settings, people, or simply alternative ideas for how things might have developed, imagining how processes might have acted differently to nonetheless create familiar results.

So what might some of these ideas look like? Whilst we always encourage true etymological nerdery, we can get a lot from coming up with alternative ideas as well. In that spirit and as examples or inspiration-joggers or simply for the sake of amusement, here are a set of entirely false etymological facts (we want to stress, none of these are true: please do not spread them as misinformation!) Maybe they'll inspire – or at least amuse...

1. The name of "rum-butter tarts" derives from Islamic prohibitions on alcohol: some Ottoman-era Turks falsely claimed that Orthodox Christian traders spiked their butter with alcohol to corrupt people from the faith, hence "Rumi butter" or "Roman butter" after the Byzantine Greeks. A mid 19th century French chef created the modern dish for a Turkish-themed masquerade, using cointreau: rum itself started being used for the food in the 1910s.

2. The verb "to enter" comes from the German Ente, meaning a duck: German traders in the past often were told to "duck" when going into the houses of English merchants due to low lintels over the doorways in England. Asking for the translation of "duck" and finding it was "Ente" (the bird), the Germans assumed this was a quaint English saying whenever someone went into a house and the association of "ente" and going inside gradually made its way into English as well.

3. The term "wallflower" has actually reversed its meaning over time: originally it is a corruption from "whale-flower", that is, the blowout spouting of a whale, and meant someone who spouted or talked far too much. The term, popular in the 18th century, then started to be used in jest or sarcasm for people who were considered too quiet, until it eventually shifted its meaning entirely and people forgot the original maritime associations.

4. The manatee, originally the "man 'o tea" due to a gentle and calming demeanour associated with the imagination around sipping the drink in question, was one of a number of sea creatures named along this format by 18th century sailors, the Portugese Man 'O War jellyfish being the other example that has survived to the present.

5. A "socket" is an Anglo-French mixing, literally a "sock-ette" - too small to be a sock, but still there for fitting something snugly into. Sockettes that just fitted over the toes and toe-joints, leaving the ankles bare, were a fashion piece in the 1610s: the term was adopted by high-class doctors later in the century to find a way to explain the action of ball-and-socket joints to their wealthy clientele, and it stuck.

6. A number of old words for movement involve a thing used or imagined in the movement - among these is waddle, the motion done by people walking on wads of thick cloth strapped to their feet as a treatment for bunions. Paddle, to push oneself along with a pad, is also in this category - a lesser known one being to boatle, which only survives now in the phrase "to bottle it" - actually "to boatle it", i.e. to run away in a boat.

7. Microphone (pronounced "My-Cro-Fon-Ee") was a nymph in ancient Greek myth in variants of the myth of Echo and Narcissus, who was responsible in some version of the tale for reporting the sad fate of the two lovesick beings to the world due to being the only one who remembers everything that Echo says despite all her words being ignored by others as repetition. Johann Philipp Reis adopted her name for his early sound transmission equipment in the 1860s.

8. The word "bully" comes from Malay "bulan" - which means the moon. Mixes of Malay and then English sailors in southeast Asia started using the words to have a deniable discussion of supervisors who pushed them around on the sea - as the moon does with the tides, so any discussion of being "pushed around" that was overheard could easily be explained away as sensible nautical consideration.

9. A probable old word, now lost, is "aff", likely a verb meaning to get involved in things. From this root we "have an affair" where we aff with someone for their fair (beautiful) nature, and "affray", to aff with someone because relations have frayed, and we "affirm" things to firm up our affing with them. Being "affable" now just means pleasant, but this developed from it meaning to be most able to aff and get involved in matters concerning others.

10. A hamlet was originally a settlement so small that in medieval tax assessments it was only noted as having one pig or fewer between all the villagers - hence, just one ham.

11. Vibia, a member of the family of the same name which produced Romans such as the emperor Gaius Vibius Trebonianus Gallus and the author Vibius Sequester, was exiled from Rome in AD 53 on a charge of asking astrologers to foretell the emperor's death. Her cause became totemic for Roman astrology, and her name thus a by-word for trying to work things out through vague or unknowable methods - hence why we look for places with "good vibes" today.

12. One of the less successful endeavours of early seventeenth century explorer Robert Dudley was a natural history treatise in which he tried to classify animals by utility to mankind, and regularise their names and terminologies accordingly. The only two animals to which he gave the highest rank were the dog, for its faithfulness to man, and the butterfly, for its beauty: whilst science has moved on, his regularisation of "pup" or "pupa" for a young stage of either remains.

13. "Paradise" is of German origin, literally a "Parade aus Eis": this stemmed from early medieval Christian depictions of heaven and hell in which there were assumed to be continuities between them as opposite poles of the cosmology. Thus, since hell was assumed to be the hottest possible place so that sinners were burned, heaven was assumed to be the coldest place in creation, a cold made liveable by grace: to see God was to walk the Parade of Ice to heaven itself.

14. Using a carpet for flooring was originally something practiced in marsh and fenland villages of northern Europe, where old or broken fishing nets - literally, carp nets - would be piled on the floor to avoid some of the damp and risk of bare mud floors. Aristocrats from the fifteenth century onwards later referred to piling middle-eastern rugs in similar fashion as "carp-net" in reference, and the modern carpet was born.

15. In the north of England in the 19th century, tools were often loaned or lent to poorer workers, some of whom relied on these tool-loansmen to ply their trades. One part of this practice was that is the worker picked the same tool ten times running, the loansman would keep it reserved for them thereafter: liking a tool enough to give it its tenth use then became known as "tenth-use-ing", which is why we now "enthuse" about things we like.

16. Contrary to popular belief, "feeling down" doesn't refer to the direction, but to the soft feathers of baby birds. The phrase was originally "feeling downy", and implies that one is like a baby bird: limited in ability to interact with the world, and frowning all the time (a look that baby birds tend to have due to the "gape" skin structures on either side of the mouth that help the adults feed them).

17. To have "aspirations" comes from the asper, a medieval silver coin type especially used in the late Byzantine world of the eastern Mediterranean and Black Sea. Someone who wanted "to seek aspers" - that is, to go and find their fortune as a mercenary or trader in the wealth - was seen as implying a willingness to take high risks for potentially great rewards.

18. "Eyaaaa" used to be the standard English way to write a shout of pain or frustration. The modern, more familiar "Aaaagh", derives from British Imperial rule in India and "aag", the Hindi word for fire: it became widely known and popularised after a number of colonial administrators died due to failing to realise that locals were telling them about a fire that had started, which led subsequently to an increased awareness of the term among the colonisers.

19. One North African legend about the hoopoe, upupa epops, was that if you could get it to sit within a circle it would tell you who you were going to marry. People and especially young women thus brought loop-shaped perches to entice the birds and these "hoopoe rings" or "hoops" became a general term for larger ring-shaped loops of metal: the term was carried back to Europe both through trade and through an early 18th century Italian fashion trend for "hoop" earrings.

20. The gazebo tent, with openings on all sides, was originally set up as a way to allow ladies at some more risque and fashionable sixteenth century jousts to get a better view of the knights as they headed out to the lists, rather than just seeing them from the front whilst they fought - hence, a gaze-your-beau tent, and the modern gazebo was born.

Why not come up with your own ideas along these lines? Do comment good ones below, we'd love to see what you come up with. We hope these in some way amused you or poked some thoughts into being that might not have been there otherwise. Happy wordplaying!

Pasts and Playfulness: Protecting Fantasy from Fascism

September 25, 2022, 01:55:10 PM

It's no great secret that the European and North American far right are very keen on the medieval period and medieval aesthetics. From DEUS VULT emblazoned on flags at the storming of the US Capitol last year, to anti-Islam imagery coming with , to 'viking' or 'pagan' masculine imagery being used to promote 'traditional' family structures, there are many permutations and combinations out there.

This far-right use of medievalism – the correct term for imagined-medieval aesthetics, not all of which come with true medieval pedigrees – comes along a number of lines which are often conflated. There's crusade imagery, often appropriated within a 'clash of civilisations' narrative that presents. There are also religious-traditionalist images, often part of narratives around the supposed high or elite culture of medieval polities that is seen as having in some way degenerated (the Byzantine History-Far Right links are often in this area). Then, somewhat in tension with the former images, there's the sort of 'grimdark enlightenment' view that sees a gritty, violent, hyper-masculine and often implicitly or explicitly non-Christian northern European culture with rigidly enforced social roles as an actively good and aspirational outcome. It imagines a past in which individual masculine dignity and a counterpoint submissive, protected femininity are restored by a revival of strength and 'pagan' cultural elements.

|

|

This is a complex area but the above outline will do – what I want to talk about in this article is how those of us engaging in creative pursuits that use medieval ideas and aesthetics can push back and undermine these people through our work. I'm axiomatically assuming that's a good idea, and that part of it is in the work itself. We obviously can, and should, push back at a meta-level as well by rejecting these people's claims: but I think it is also good when we can build wider and more interesting medieval worlds that are less simplistically easy for these people to hang their hats on. That both means not providing them with models of the past that chime so easily with the world they want to portray, and it means contesting their claims to aesthetics, imagery, and people as for example "White", "Nordic", or "Anglo-Saxon", all terms that the far-right often use somewhat ahistorically and interchangeably to represent their ethnic and cultural ideals. These cross over both things that purport to represent history and fantasies that are justified by reference to that history – indeed, these things are actually a sliding scale in any creative work or representation.

In any case, I'm mostly going to focus on creative work here, more than about attempts at writing actual history: one can get sucked forever into the minutiae of why particular historical views held up by the right are muddled, wrong, and misread, and I don't intend to wade into that in this piece. Instead, I'd rather focus on how we build medievalist ideas and aesthetics that are harder to appropriate and which help undermine far-right presentations of the medieval period in different ways.

I think one of the best ways to counter the sort of hyper white "Saxon" imaginary (examples shown in in the image screenshots here) is finding smart ways to play with it. Writers, artists, game developers etc can do a lot to shake and subvert far right claims on & about these imaginaries/aesthetics. We see even for pure fantasy settings many arguments about what is and isn't "realistic": really they're about what feels authentic, not about historical facts, though these relate to each other. But expanding that authenticity space to embrace more of human experience is vital. Essentially, we end up somewhat mentally trained to particular sets of expectations that certain things go together – and we should see those sets of things as arbitrary and malleable, they're something that we as creators can and should actively work with.

Tales of medieval demon-fighting heroes need not be centred on Europe. British Library Add MS 5600.

Engaging with people and texts about places and mythos more widely is critical: whilst the European past was considerably more diverse than the desperate imaginaries of a racist minority, it's also important to recognise that even in that period this was not a disconnected world and that portrayals of the period need not be confined to a region that was rather a backwater in terms of Eurasia at the time. Other people seeing themselves in the past is partly a matter of "hey that guy has a face shape and hair like mine" but it's also importantly about people finding their stories and their families' stories in the imaginaries we build. These things help build on one another, too: the stories and names and tropes that make the medieval less European-centred may make it more familiar to some people globally who the Whites-Only Middle Ages types want to exclude, but will also make it less familiar to those versed in the standard medieval and fantasy tropes of the Anglosphere. That unfamiliarity is good! It's fun, it stops settings becoming moribund, and it arguably presents better a world that had a potential for unfamiliarity greater than our deeply information-connected present. When I write medieval fantasy tales and games a lot of my characters whose pseudo-cultures are not very European are the result of me reading some piece of mythos or medieval text or history book where I thought "you know what – that's really cool", and that mix of enthusiasm and authenticity tends to work well.

I think another route which also works with the idea of unfamiliarity is to play more creatively with how weird and playful imagined pasts can be. For example I run early medieval fantasy TTRPG games that often focus on getting players to explore concepts and ideas like guest-rights and their importance. This helps combat the simplistic far-right version of the hypermasculine middle ages, in that it erodes the ideas of masculine authority and strength at the expense of the highly developed social rules and norms that people grappled with in the period. Similarly, portraying vassalage and manorialism and their very real quirks can erode the idea that medieval countries were simple precursors to modern states with their "nations" already formed. Appreciating how political and ethnic identities might not connect as neatly in a world where allegiance is fundamentally to a person not a state makes it harder for people to then accept appeals to 'national' moments in the medieval period as directly connected to the struggles of modern countries. Right-wing societal "values" of insular opposition to travel and outsiders, absolutist relationships with religion, and nuclear man-centred households don't make sense in a medieval world: a complex, human pseudo-past society that needs to talk through its problems doesn't let them take that space.

(As an aside, when talking historical games I often emphasise the "how" as well as "what", society & process as well as the aesthetic, and thus why code, quest design and narrative structure are useful to consider more. The above is one good reason why that massively matters).

"Remember what they took from you!" works a little less well as a caption for this picture.

British Library manuscipt, Royal 10 E IV f. 122.

A final thought on an idea that resonates overmuch in fiction: the connection of blood and soil. This is (perhaps especially in Europe) a very core part of white supremacist ideals, the idea that essentially peoples are inherently connected to places by blood and culture. It's important to actively pull this one up by the roots, but it still appears played-straight in far too much fantasy, especially with the wider fantasy focus on bloodlines and inheritance as a way of passing down various forms of magical power or bond (one of my least favourite parts of Haven & Hearth, a game I generally love, is the fact that the land claims in it are referred to as A Bond Of Blood And Soil).

I think for this we should engage explicitly with ideas of nature and home, what it means to choose a place and expanding spaces of belonging so their claim doesn't land. We can and should make worlds and fey and woods and hills that explicitly reject blood claims upon them. There are any number of ways that things can be fated, and medieval rules of magic are often explicitly bizarre – check out just about any geas in a piece of Irish literature, half of them are rules like "you must never have a drink under a full moon, never eat soup at the same house twice, and never dance when there are more than three dogs in the room" or similar. We don't need to make things entirely random, either: there's no reason why someone's personal, individual connection to a place or site should be derived from blood rather than being a personal characteristic of that person.

I will note that I'm not saying every work has to do all these things, all at once, and I'm definitely not saying there should be some wide shared agenda for what fantasy and medievalism should look like. What I want here is to say exactly the opposite: that taking medievalism in different directions, both digging deeper into the complex humanity of medieval material and thinking explicitly about when and where we use and reject that material, breaks medievalism out of the box and keeps it growing in a way that both offers huge storytelling potential and less fertile ground for people who want to use these symbols for their extreme misinterpretations and ideas. Making it difficult for the far-right to put their roots into medieval ideas generally also creates the space for a lot of the current common tropes and symbols of medievalism to be part of our stories and imaginations without dominating them: a bigger, more human scope for medievalism is good for everyone.

I hope you've found this brief discussion interesting – please do feel free to share your thoughts and ideas on this complex and growing area in the comments. Building complex, exciting, messy and human fictional worlds is something where we can all learn from one another: it doesn't have to mean trashing or abandoning the things we love about pseudo-medieval worlds, indeed it's the continuation of the process by which they were made. Our love of the quirky, the small, the strange and the ancient – that which cannot be made to conform – has a power, and it's one that those who want the world to fit into cruel, bland boxes should, very reasonably, fear.

Acknowledgements and thanks for this piece coming together should go to Kat Fox for coming up with the original screenshots, Dr. Mary Rambaran-Olm for her discussion of them on Twitter, and to Thaheera Althaf for reading over this piece, extended from an original Twitter thread of mine, before publication..

A Bad Pun RPG Idea Calendar

January 02, 2022, 12:25:32 AM

So, recently on Twitter I foolishly said that I would post a pun-based RPG plotline idea for every like on a tweet. I am nothing if not true-ish to my word, and as the likes piled up I ended up producing over fifty of the things as the month of December 2021 wore on... and having produced that many, I decided there was nothing for it but to reproduce them in article form. And how better to do it than a 2022 calendar?

As such, here it is, with one awful pun-based idea for a sidequest or subplot per week for the entire year of 2022! Check out your birthday or other significant dates through the year for maybe-or-maybe-not appropriate puns galore, or just browse to find interesting ideas for your upcoming creative projects and campaigns. Or because you just want a lot of groan-inducing humour in your life, that's fine too. And thus - the calendar!

THE PUNS

Jan 03 - Jan 09

Evil wizard Butho Cai will try to create the Thousand Coloured Robe of Fate amid the the Ancient Looms of the Hill of Fading Time.

Will you stop him, or all perish? Fight cloth demons, unravel traps and find out in this adventure because it's a WYRD HILL TO DYE ON.

Jan 10 - Jan 16

Dragon-hunters use hawks to track their mighty prey - and you've just found one in a snare. Will you return it, losing time and maybe the huge bounty? Or keep pushing on and leave the bird to its fate? Your choice will have consequences in THE EARLY BIRD GETS THE WYRM.

Jan 17 - Jan 23

The Ship of Dreams carries the Elder Kin from world to world and plane to plane, powered by the dreams of a mortal who broke a fated duty. But now it's crashed in the mortal world: its pilot has escaped, and the Elder Kin raid to find him, desperate to leave, in OUT OF GEAS.

Jan 24 - Jan 30

A herbalist has grown the world's first hardy all-weather mandrake, but is under pressure from the King to hand over the secret and makes no secret of his distaste for the monarch's plans. Can you save him from the royal guard in A MANDRAKE FOR ALL SEASONS?

Jan 31 - Feb 06

You awake. Sheogorath is there. You see a bubble of abstract madness. Fifteen glowing atronachs pop in and out of existence. You wander in the nest of a moth. You sleep. You awake. Sheogorath is there. You see a bubble... welcome to GROUNDHOG DAEDRA.

Feb 07 - Feb 13

You know you did nothing that would merit this - but you've awoken in a demon's lair anyway. Are you being framed for consorting with demons? Who is responsible? And... might it not be somewhat fun even if you are? Face death and lust alike in THROWN UNDER THE SUCCUBUS!

Feb 14 - Feb 20

Sir Everhorn is a legend among knights: appearing and disappearing like the wind, saving the lives of folks who he will never see again. But can the heroes get him to commit to protecting the people for a longer term? Why does he roam eternal? Find out in ONE KNIGHT'S STAND.

Feb 21 - Feb 27

A young lady had a romantic tryst with a Selkie three summers past. Now the Selkie has left her for another, but she's still magically, inexorably drawn to the sea. Can you break the curse? Or might she still find true love in the water? This and more in SEALED WITH A KISS.

Feb 28 - Mar 06

Dwarves are notoriously secretive, their protections against Watch snooping absolute. When Elder Bastrom fears corruption in the Diggers' Guild, then, she needs you to join the guild & investigate. Can you thwart the plot? Only if you've successfully MINED YOUR OWN BUSINESS.

Mar 07 - Mar 13

A document has surfaced proving that a mere farm-hand must be the heir of the famed Beowulf. Now he's come to you: he's been exalted as a potential hero, but he doubts the document is real and has no idea how to fight a dragon. Will you help him manage GEAT EXPECTATIONS?

Mar 14 - Mar 20

Rumours of the Lost Dwarf Forge prompt streams of would-be heroes to investigate. But are the young warriors being lured out for other reasons? Why don't they return? Are the best weapons the ones you had with you all along? You'll learn more in A HALBERD IN THE HAND...

Mar 21 - Mar 27

The Host of the West comes. All forces of darkness quail... and you are one of Morgoth's lieutenants. You must devise & enact an escape plan to allow your master to flee to hiding and waylay his mighty siblings, in DISCRETION IS THE BETTER PART OF VALAR.

Mar 28 - Apr 03

In 972, you were sent to the Howling Jail of the Elfin Lords for a fairy crime you didn't commit. You escaped: still hunted, you survive as tricksters of fortune. Now someone has a problem and no one else can help: and they've found you. Maybe they can hire... THE FAE TEAM.

Apr 04 - Apr 10

Two murders: a jilted love affair, an ensuing blood feud. Such happens in the blood-dark of a cold marshland winter. But these ghosts are unquiet: the locals think the souls refuse to leave, but you know powerful ritual magic binds them here, in TWO WRONGS DON'T MAKE A RITE.

Apr 11 - Apr 17

Lightning rolls. Two shepherds drunkenly stumble off the moor: each blames the other for the howling banshee that has been unleashed from the Auld Stones. Who is right - or is their enmity hiding the real tale? You must face the truth this time in KNOWING MEAD, KNOWING EWES!

Apr 18 - Apr 24

Preachers roam the streets chanting about the Great Floods and urging you to drive back the evil water spirits. Doom seems nigh indeed: outlying villages have been washed away. But are the water spirits solely to blame? It's time to wade into the problem in THE END IS NAIAD!

Apr 25 - May 01

A musician is forced to leave her home city of Dassalora permanently after inadvertently causing a riot. She turns to you for help clearing her name: the Council may be willing, but they have other problems to solve. In BARD FOR LIFE, see if you can help her return to fame!

May 02 - May 08

A noble believes his harvest will be the realm's finest, and has invited the king to stay. But, some say as punishment for hubris, a cockatrice now ravages his lands. You are called in: can you find the cockatrice's vulnerability and save the visit in COUNT, YOUR CHICKENS?

May 09 - May 15

The rules of troll fights are intricate and hard for humans - and then there's their strength. But now a huge young lady from from the hill clans demands your village beat her fairly on the village green or give her a husband. Will you play fair when BRAWLING A MAIDEN OGRE?

May 16 - May 22

The great bird has come to your mountain realm. It carries off the great markhors and elephants, and threatens all the herds of the kingdom. You must find a way to save the region's wildlife by travelling to the barren, rocky mountaintops in BETWEEN A ROC AND A HARD PLACE.

May 23 - May 29

You'd expected Devils to be hellish, enforcers of rules. You hadn't expected them to be so parochial. A carnival of demonic evil would be one thing: standing in perfect, recorded line to play hoop-la for your soul is somehow worse. Can you survive A FETE WORSE THAN DEATH?

May 30 - Jun 05

The Monster tears - again - a rift between Daevic and Mortal realms, unleashing curses into both. As you investigate, you find the source of its pain and realise why it it cannot rest. Can you find a way for it to exist at peace? Test your heart in THE BEAST OF BOTH WORLDS.

Jun 06 - Jun 12

The trail is cold: Geralt's investigation of a curse in scrolls and notes is fruitless. But the first witcher who took the contract is missing & could have seen more: perhaps finding him is Geralt's only hope in A WITCHER IS WORTH A THOUSAND WORDS.

Jun 13 - Jun 19

At the Grand Archery Tournament, a stray arrow that missed the target has shot Prince Muskwort, who is critically ill. The archer uses his own distinctive arrows... but he and the crowd swear he was facing the other way. What's the truth? Find out in HIT OR MYSTERY.

Jun 20 - Jun 26

A fae message comes from Orion, King of the Hunt. Against Forest Law, he refused to kill a magic talking stag he loved but was fated to slay: it lives wounded and hidden. The breach of law would tear the fae court apart. You, an outsider, must decide who is left HARTBROKEN.

Jun 27 - Jul 03

Rebellion and civil war loom. One last social event, the Dance of Summer Moths, will bring partisan lords together: the Great Temple wants YOU to host it & avert all-out war.

Expect intrigue, romance, murder: how you react is crucial, because THE BALL IS IN YOUR COURT.

Jul 04 - Jul 10

A fad for demon possession? You can't believe your ears, but the archmage nods. Locked in their tower, mages hunger for anything that gives strong feelings: and demonic anger is truly strong. What can men do against such reckless hate? It's ALL THE RAGE right now, after all.

Jul 11 - Jul 17

The story of Icarus' death and the wax on his wings is well known, but is that all there was to it? Having discovered Daedalus' notes you realise Icarus was never meant to land safely - and that you must journey to the sky yourself to find the truth in LIKE FATHER, LIKE SUN.

Jul 18 - Jul 24

You are in Saruman's retinue in Isengard. You've been told to oversee work in Fangorn.

A promotion? ...or is someone getting you out of the way? You might very well think that, but the events of I COULDN'T POSSIBLY CALM ENTS will determine your survival.

Jul 25 - Jul 31

A team of Dwarven thugs are operating in broad daylight in your outpost town: worse, they have a signed order from King Bhelen's governor giving them wholly free rein for whatever they wish to do. Stop their plans and expose corruption in CARTA BLANCHE!

Aug 01 - Aug 07

You dreamt of being Chosen by a god as a scarred urchin on the streets. Now it's happened! But... rather than the great war or death gods you've been Chosen by Aheria, Goddess of Beauty. Where fashion sense is sacred, tread a path from sacking to silks in BLESSED TO IMPRESS.

Aug 08 - Aug 14

Cave lions as a rule don't come into the cities, but folk in Krahlek keep hearing them. When you investigate, it turns out this isn't just a wildlife problem and that the merchant guild is involved - and that it may not be clear who to side with, in DOING A ROARING TRADE.

Aug 15 - Aug 21

A silvered blade: it strikes fear, and also a lot of sharp metal, into the heart of monsters. But the anvil that made them is lost. There's one upside: that gives YOU a shot at real glory. Venture to the clouded isles and find the forge where EVERY SWORD HAS A SILVER LINING!

Aug 22 - Aug 28

The city-states of the Autumn Isles are a political tinderbox. A priest relays to you a divine command: to help two lovers from rival cities to elope. But far from calming things, this may ignite the flame of war... defy the gods or risk slaughter in A MATCH MADE IN HEAVEN.

Aug 29 - Sep 04

The people of Lyrendorf are terrified of the Myrken Woods, where dryads wander and folk hear chanting under the moon. But now the Woods are sick - and the same illness threatens the harvest. To save either side, you must get both to work together in ALL BARK AND NO BLIGHT.

Sep 05 - Sep 11

You're fey creatures, and a human has wandered through a portal to your realm. He looks exhausted and sad, avoids talking & refuses aid. The Fairy Queen Siannura gives YOU the task of helping him learn to hope again and become a hero. It won't be easy to TEACH A MAN TO WISH.

Sep 12 - Sep 18

During the mage rebellion, a hunter comes across a wrecked shrine and the aftermath of a summoning gone wrong: he flees with the dead wizard's valuable supplies. An old templar and a desperate apostate are on his tail, though, in NO CHANTRY FOR OLD MEN.

Sep 19 - Sep 25

Dragons navigate by scent: when the king orders you to catch the Green Wyrm of the Hills, mixing a dragon-breath like gas lure is your best bet. But keeping the alchemical mix stable will be hard & while you stake it out you'll be vulnerable, in A WAIT WITH BAITED BREATH.

Sep 26 - Oct 02

The dead are rarely called on as heroes. But Sir Hordavan cannot be buried until he completes his list of side-quests: he is clearly no longer able. His will names you as champions in the event of his death... descend into the Deep Caves & finish his work in SIX FEATS UNDER!

Oct 03 - Oct 09

What dark deeds linger with those who one fought the Darkspawn? Are you willing to tear memories from the dead to find out? Few Wardens get marked graves... so you, and a troubling mage companion, venture to the Deep Roads to find the SHADES OF GREY.

Oct 10 - Oct 16

A flesh golem, brought to life by great lighting rods, is being hailed as a miracle of a new scientific age and the bringer of perfect truth. But you suspect the creature is being manipulated into parroting messages from a secret cult: can you change its tune in VOLT FACE?

Oct 17 - Oct 23

The town's household spirits are disappearing, sneaking off to standing stones, up old trees and down crumbling wells. What draws them there? What links these locations? An adventurer like you will be needed to examine THE BROWNIE POINTS and find out... before it's too late.

Oct 24 - Oct 30

Due to a problematic legal technicality and an army from its own eukaryotic kingdom, the Grand Overfungus now rules the Kingdom of Soko. You can't risk all-out war: you must persuade the Overfungus to leave before Soko is awash with mushrooms in WHEN IT REIGNS, IT SPORES.

Oct 31 - Nov 06

They believed it useless. A revenant too big to lurk in the dark, too slow to evade the witch-hunter's torch. Abandoned by its undead kin, it lay born of undeath's hubris.

But now the WIGHT ELEPHANT is back. It trumpets vengeance on the deathless: but the living fear too...

Nov 07 - Nov 13

Phoenix feathers are rumoured to have a thousand magical uses: but none in this age has ever stored a full feather and survived the bird's rage long enough to study it. Can your team be the first to return one to the alchemy guild? Burn your way to glory in in TAILBLAZER!

Nov 14 - Nov 20

The siege of Taraness drags on after years, due to a curious problem: the city keeps magically moving around the attackers! In the siege camp, you've towers and weapons but little hope: can you come up with a plan & capture the city? Have you tried TURNING IT OFT, AN ONAGER?

Nov 21 - Nov 27

Cantankerous Sir Kay was never friendly with young Sir Gareth - but tricking the former kitchen servant turned knight into being indebted to him seems a bit harsh. Can you help Gareth out and solve the intergenerational dramas of Camelot in OWE KAY, BEAUMAINS?

Nov 28 - Dec 04

Food delivery, a Viziman noble's new fad: but now a Witcher is called. A man is dead: insectoid monster eggs, ready to hatch, were snuck into the food parcels! Team up with a sorceress in training to get cake delivered safely in KIKIMORES DELIVERY SERVICE!

Dec 05 - Dec 11

A wealthy noble has had some items stolen - he won't say what, but still wants you to find them. You find they have been fed to mimics - but why and what secrets do they hold? Discover the answer in GET IT OFF YOUR CHEST.

Dec 12 - Dec 18

The ferocious Snowbound Order of Nuns lets no initiate leave their ice-monastery: but an old friend was, while habitually drunk, tricked into the magical joining ritual, and is desperate to flee. She sneaks a message to you: can you help her escape, so she can KICK THE HABIT?

Dec 19 - Dec 25

Midwinter brings a mysterious stranger with a set of musical instruments to the castle door. She hails from a land of burning sand, and wishes to find her way home, granting you three wishes for doing so. Can you find the true spirit of generosity in THE DJINN GIRL'S BELLS?

Dec 26 - Jan 01

A carpet merchant hires you to track down goblinoids who stole his stock - but they've fled into the Caves of Frost Eternal. You must fight not only the beasts but the cold too as you build a camp in the frosty tunnels! Can you be...

AS SNUG THERE AS A BUGBEAR IN A RUG LAIR?

And that's your lot! Happy New Year, dear reader, and I hope this bout of silliness has added some joy to a world that always needs more of it. Take care, let me know in the comments what quest you'll be doing on your birthday, and have a wonderful 2022!

Riddles on a Cold Moon

October 31, 2021, 10:46:30 AM

It's the time of year for moonbeams and shadows in the dark, the dying of summer plants and the turning of the seasons: a time for warlocks and silvery ghosts, the wakened dead and unhallows all. Yes, it's All Hallows' Eve, and so here's a special set of autumnal or dark themed riddles for you to try out. All of these were written specially for the season this week, and it's up to you to puzzle out the answers - if you dare, that is...

'Twas you stole my unborn, you who slashed me apart,

And you too must be blamed for my burning heart.

Though you strive by my start iron and water to bend,

Your brother and mother will meet my end.

Riddle 2.

I once took gold from powers on high,

But lost my purpose when night drew nigh,

I'm often torn from gnarled, hard limbs,

And teeth rip at me on beasts' dark whims,

Til' when nights turn to deathly cold,

I fall: I turn to dust and gold.

Riddle 3.

I protect all that's you, be you peasant or earl,

Be you bard who would raise me to speak of a girl,

Unless I am naked, to name me is rare,

And when I am naked, no name comes from there,

So I wonder the reason for your unease?

I'm a mere memento, plus, that which sees.

Riddle 4.

Legs needed I none to give wisdom's euphoria,

But I've four if you find my home under Victoria,

I'm in the precise things you needed to know,

I'm done unto eggs: say my name, and I'll show,

And if you're now stumped, if there's aught you require:

Let's make a deal – I know you've what I desire.

Riddle 5.

Those said to be like me may wheedle and flatter,

But my biggest lie – it's not me holed in batter.

Though my cousins found fame on the Owl-queen's town's stage,

And dropped on two crowns through a sky-threatened rage,

I've not got their complexion, but I'm doing just fine,

So if you stayed in check, then I'll be at the line.

Riddle 6.

They made me from that which was dead,

They bound my fingers to make my head,

My namesake's robed in gold and green:

But I grasp dirt they don't want seen.

And I am grasped in turn, and rise,

By these unhallowed hands and thighs,

My head, from dust, thus seeks the skies.

Riddle 7.

These tired rivers now flow blue,

They say, for kings, they always do,

But not for you and I, my friend:

The proof can come from blades that rend,

Though they sound much like preening pride,

You need these rivers, deep inside.

Hope you enjoyed these riddles! Feel free to comment answers, ideally in spoiler tags, below. If you enjoyed this riddle set, do check out our regular riddle thread for the latest unsolved puzzle there! Stay scary, and have a suitably happy, or horrifying, Hallowe'en!

Apocalypse Now, Or Never: A Brief History of The End of the World

October 27, 2021, 07:09:07 PM

"The world is in peril. You are all that stands between the gathering darkness and the fragile lives of every-day folk in villages and cities scattered across the lands you know as home." If this situation sounds familiar, well, it probably is. The total and existential threat is a classic of fantasy stories, gaming and is an exceedingly common trope in modern fantasy RPGs, both computer-driven and otherwise.

There are various minor variants on apocalyptic showdowns: what "destroying the world" literally means, whether it's a black hole or turning the planet into a demon-only hellscape or simply a thousand years of oppression by brutal dark overlords, can vary. What all of these things fundamentally share is that they are worse than anything you or any regular actor in the setting can imaginably do. No regular despotic tyrant could even envisage this sort of power: and that's why you have to stop it. There's no question of where it sits on your to do list (at least in theory), because if this doesn't get done then you won't have a To Do list.

In this and hopefully one or two subsequent articles, I'm going to take a look at the end of the world, where it fits into our fantasy settings, and some problems with using it that we may or may not be able to solve. I'm mostly going to focus on ends of the world that are mythic or intentional, such as tend to fit into classic fantasy settings, rather than mass depopulations and post-apocalyptic waterless wastelands. In this first part, I'd like to take you on a whistle-stop tour through the history of the apocalypse, and we'll see if we can find one or two interesting things to discuss along the way...

Facing down the apocalypse has a long history: the first imagined apocalyptic event in known literature is possibly Ishtar's threat to release the dead to devour the living in the Epic of Gilgamesh (though this is a threat to ensure she gets to provide her preferred albeit technically lesser punishment to the epic's heroes, specifically releasing the monstrous Bull of Heaven on the city of Uruk). It's notable that whilst the Bull is defeated, Ishtar isn't – ultimately, in ancient societies, apocalypse is in the hands of the gods more than mortals. We see the same in the medieval Eddas' tellings of Norse mythology, where Ragnarok is specifically a conflict between gods, one in which others may fight but ultimately a cosmic inevitability. Christian revelation, likewise, is an apocalypse of gods, not of heroes.

Indeed, we might even suggest that an apocalypse the protagonist can get involved with and one only the gods can manage are semi-exclusive: a genuine world-ending scenario to be defeated cannot so easily be envisaged when it's a tenet of faith that there is one specific world ending, which has already been mapped out and is core to your religious understanding of the world and its cosmology. You may be on the look-out for symbols of your pre-existing apocalypse (and there have been, to put it gently, a lot of false start calls on those over the years) but it's harder to then invent or conceptualise other literary apocalypses.

Another feature of apocalypses as imagined in religion and myth is that they are frequently in some way punitive, a setup for the next world, or both. That is, not only is stopping the end of the world not a thing you actually can do, but it's a thing that would ultimately be bad if you managed it. Either that or they're mainly to be combatted through fundamentally internal, moral struggle: the external problem is a consequence of moral failure. See for example Dr. Eleanor Janega's notes in this post on Jan Milíč of Kroměříž, who did believe the apocalypse could be delayed, but only through fixing what he saw as the moral and social failings of his contemporaries, in particular re-instating a harder line on clerical celibacy and establishing a more powerful, unified, Christian empire at the heart of Europe. The changes he sought were ultimately socio-political, not individual and heroic, in character. The concept of the end of the world coming alongside a general degradation of humanity that necessitates its destruction can be seen not only in Abrahamic faiths but also in for example Vaishnavite Hinduism (where at the end of the Kali Yuga, our current age of decay, the incarnation of Vishnu called Kalki will come and rally the righteous to purge the world of evil). Both Vaishnavite and Norse eschatologies, along with others like that of Zoroastrianism, also include the concept of a post-apocalypse world better than the one that passed before being formed after an almighty final battle.

So, whilst the end of the world has a long history, for most of it there hasn't been a lot for heroes to do with it other than perhaps get judged with the rest of us or turn up as groupies for whichever deity is purging the unrighteous. Or at least, that's mostly true: apocalypses as world domination, rather than as world destruction, are a slightly different matter. Even these are quite rare in classical and medieval texts (with the usual caveat that my knowledge is relatively Eurocentric in these matters). An exception would be some (though not all) western medieval treatments of the Mongols. Writing in the thirteenth century, the Franciscan friar Giovanni di Plano Carpini assured his readers that "The Tartars mean to conquer the entire world if they can... it is said, they do not make peace with anyone unless they submit. Therefore, because except for Christendom, there is no land in the world which they have not taken, they are preparing to fight us." The concept of a mighty threat from the east which must be resisted at all costs is in some ways an echo of ancient Greek writers' views of the Persians, but when added to the religious, moral threat that someone like John saw in the Mongols, we move from invasion to apocalypse: in a future dominated solely by the Mongols, there will be nowhere in the world left to run to. As Giovanni puts it, "it is not fitting that Christians should submit to the Tartars because of their abominations, and because the worship of God will be reduced to nothing and their souls perish and their bodies be afflicted". Not only moral risk to the soul, but physical corruption is hypothesised as the effect of the Mongol advance. In his account the Mongols are somewhere between the human and monstrous: beatable as long as Christendom unites in time and adopts the right methods for dealing with the threat, but a threat on an existential and spiritual level, nonetheless.

These templates of world ending as conquest and world ending as true apocalypse are brought together in the grandfather work of modern fantasy – Tolkien's Middle-earth. Sauron is an apocalyptic figure, well beyond the potentialities of any human ruler, and physical and moral corruption is core to the systems of his power. There are echoes of John of Plano Carpini in the presence of orcs as corrupted peoples (exacerbated by Tolkien's private descriptions of them as 'mongoloid', one of the more awkwardly racist notes in the Professor's conception of his world). There are echoes, too, of the extent to which uniting against him is key to his downfall. Middle-earth, though, is a heroic fantasy, and this unity can be built by a small number of exceptional individuals. It is important to Tolkien's conception of Sauron that he is small on a cosmic scale: even his master is in truth only of a super-angelic rank, with the real eschatological muscle in the hands of the creator. Ultimately, though, Eru Illuvatar is a more modern sort of God: a background figure whose ultimate justice does not prevent proximate world-ending catastrophe.

Tolkien wrote against a backdrop where the end of the world had come closer to home in literary terms. The genre of apocalyptic and post-apocalyptic fiction had developed through the nineteenth century in English & European literature, though most of these works covered ideas of natural (or divine) catastrophe and the possible aftermath situations. A turning point to note was perhaps H.G. Wells' 1898 The War of the Worlds – one of the first modern works in which ultimately, though not due to its heroes, the apocalypse was both driven by a sapient, intentional force, and also lost. An apocalypse that could be defeated: the path for the modern heroic fantasy was open.

In the 1970s and 1980s, the dawn of fantasy gaming created new demand in the apocalypse market – we'll look in the next section of this series at why apocalypses are such a useful plot driver in games. It was now more socially acceptable (the so-called "Satanic Panic" notwithstanding) to reincorporate demonological works and other aspects of Christian and mythic eschatology into fantasy literature and games, with the additions of Moorcock's concepts of Chaos and some aesthetics from the eldritch works of H.P. Lovecraft creating a wide range of looks already associated with end of the world scenarios that writers could draw upon. With fewer religious themes in these works, too, the apocalypse had lost its sense of providence and possibility: the pathetic-aesthetic protagonists of Warhammer or the anti-heroes of sword and sorcery novels invited us to consider that the end of the world might not have anything better after it, and if it did, well, what was the chance of scumbags like us being among the morally pure elect?

Bringing mythic and weird fiction elements into apocalypse fiction for modern fantasy audiences meant changing them to fit, however. In particular, it meant humanising and rationalising concepts and creatures that were primordial, unknowable, or defined by a fundamentally pre-set place in a story in their original contexts. Rather than being primarily intangible threats to morality and the soul, to become drivers of an apocalyptic story demons also need to become tangible threats to material reality. Pulled out of their original context, demons (and, in a different but not wholly dissimilar way, elder gods) could become far more present, tangible forces of destruction ready to destroy the worlds we know, rather than primarily forces of temptation and corruption that undermined them from within. For this to make sense, in many cases the aims of apocalyptic villains needed to be changed to more tangible and material ones - actions that a heroic character or characters could then fight back against. Gods were either elevated too high above the picture to influence it (as per Tolkien), removed entirely, or reduced to the point where they, too, were at risk from the course of events.

There are now more pieces of apocalyptic fantasy game and fiction than any one writer can cover, but this pathway to the present highlights a few features of how they got that way. We've seen how apocalyptic events were once more the preserve of the gods, and how the presence of a pre-defined idea of apocalypse in faith might be a barrier to telling other tales of the ends of the world. We've seen that eschatological apocalypses aren't always evil or created as evil acts: they may be punitive, but this comes as part of the ultimate destruction of evil and sin. Giovanni di Plano Carpini's ideas of the Mongols offer them as an alternative premodern view of absolute destruction, one that can be resisted, though one also tightly bound up with ideas of faith, monstrosity, and moral risk.

In modern fiction we've seen how some of those ideas of corrupted monstrosity and ultimate moral hazard recombine in Tolkien's apocalyptic antagonists, after a 19th century surge of interest in world-ending scenarios – and then how the reintroduction of classically demonic or new eldritch aesthetics and their increasingly tangible position within fantasy worlds created the scope of apocalyptic possibility that's easily available to fantasy writers today.

So, welcome to the apocalypse – I hope you've enjoyed the few thousand years it's taken us to get here. In the next article in this series, I'm going to write a bit about why the apocalypse is so useful in modern fantasy and game writing, and question whether there are alternative ways we could use and frame it outside the ones we use so often. See you then!

This is the first part of a series. You can read part two, Apocalypse Always, here.

Seven More Things to do with Giants

October 24, 2020, 12:36:43 PM

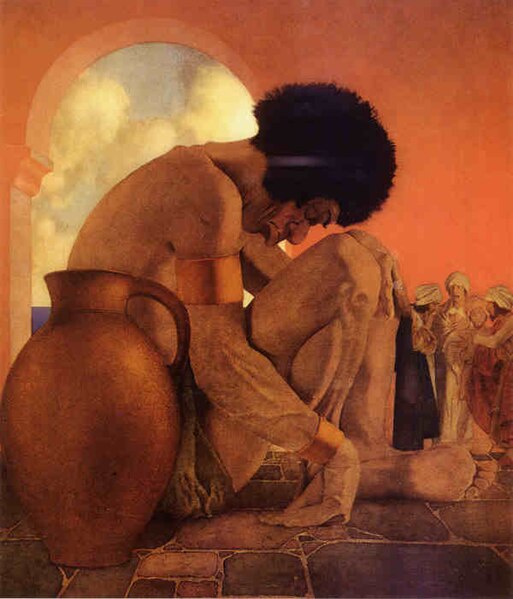

Sinbad Plots Against The Giant by Maxfield Parrish

Used under CC license by, Maxfield Parrish (1870-1966) .

Giants are a core part of many fantasy settings, and there are very good reasons why. Literally larger than life, giants are a core part of mythologies worldwide. They provide over-size mirrors for us to hold up to ourselves, with our passions and our best and, more often, worst sides oversized along with them. Whilst there's a fairly standard fairytale giant that commonly appears in fantasy settings - big, brutish, kicking houses down and getting outwitted by farm-lads - the possibilities of giants are actually much wider across world folklore and literature. In this article I explore a few more options and thoughts on how you can use giants narratively to best effect, whether for an RPG, a story, or anything else you might be working on.

A few of the other items in this article draw upon folklore from parts of the world outside the Anglosphere and Western Europe more generally. Giants are often assumed to be the creatures of a standard jack and the beanstalk narrative, usually presented, but a huge range of world cultures have some sort of giant myths, and not necessarily ones in keeping with our standard understandings of giants as brutish antagonists.

Jack escaping from the Giant

Used under CC license, Printed for B. Tabart at the Juvenile and School Library, No. 157, New Bond-Strict. Wikimedia.

In Somali folklore for example giants like Biriir ina-Barqo are heroic characters: it's perhaps a peculiarity of western myth that whilst super strength is seen as a good power - a sign of heroism - super size is generally seen as a negative. This need not be the case.

There's also no reason why giants can't travel, and arguably many reasons why they should in a fantasy setting. The prodigious size and appetites of a giant both give them the ability to travel and many reasons for leaving (one too many disappeared sheep) or heading for new places (how many lords would like to hire a literal giant for their army)? As such, it is perfectly explicable to have a giant who is from outside the mainstream culture sphere of your setting. One caution to perhaps give with that would be to avoid the "monstrous races" trap in which giants are solely coded as a foreign "other" to your default setting area: whilst this trope did exist in medieval writing, there's a fair point that uncomplicated use of this sort of portrayal has had a very dark historical pedigree, especially in the colonial era. Nonetheless, there's a lot to be said for portraying giants who come from a variety of different cultural backgrounds, and for upending the idea that it's necessarily the protagonists who travel to the giant rather than vice versa.

The Lion Sprang upon the Giant

Used under CC license by, Anonymous (the book by A. R. Hope Moncrieff (1846-1927) Wikimedia.

If we're going with bad giants that eat people, how they hunt is worth considering regarding their threat to other characters around them. This is one place where I disagree with Dael Kingsmill's brilliant video on giants: her view is that giants, being big, should also be fast, able to catch up with horses. There's undoubtedly a good chase scene there, but I think that it somewhat clashes with our view of giants as lumbering, and that we can do scarier things as alternatives. Whilst the giant's long legs of course would give a giant a short speed advantage, big bipedal predators like Tyrannosaurus were probably ambush, not pursuit, predators: and besides, there's a far scarier thing we can do with giants as predators, which is to scale up the predation strategy of arguably the most successful apex-predator meat-eating species in earth's history: us.

Humans don't hunt by outrunning things, and we don't usually hunt by ambushing them: we are neither faster over long or short distances than a quadruped like a deer. What we're really good at, instead, is walking. And keeping walking. And keeping walking. A prey animal can run as fast as it likes - we'll catch up eventually. We don't need huge amounts of food and can keep going for days and eventually most things will get tired before we do. Endurance predation is the hominid strategy: and giants, being hominids scaled up, could very validly become scaled up endurance predators.

Cormoran - Project Gutenberg e Text 17034

Used under CC license From The Project Gutenberg eBook, English Fairy Tales, by Flora Annie Steel, Illustrated by Arthur Rackham Wikimedia.

Dear reader, apply this to a giant hunting you and it's terrifying. Sure, you can saddle up on your horses and outride the giant: the giant doesn't care. He can still see you (an extra five or ten feet of height gives a good vantage), and possibly smell you too if we're going with giants having the blood-smelling fairytale characteristic. So he'll keep walking after you, quickly but never running - and also never stopping. Your horses can outpace him for hours: he can keep walking for days. You could try and hide, but how well can you mask your smell? You could hope the horses sate him, but do you want to negate the rest of your speed advantage? There are probably at most small settlements anywhere near, and you'll have to decide if you want to risk setting a hungry man-eating giant on innocent villagers for the slim chance offered by safety in numbers.

The endurance hunting giant presents a more tense, longer-term potential threat, and a difficult tactical and moral situation, and I personally tend to find those more narratively interesting than a rapid chase - your mileage may vary, but it's an option to have in mind.

Humans' inevitable reaction to tiny things is to find them cute. If confronted with an entire village full of waist-high or knee-high people, many people's first instinct would be to see them as children. Especially if you're not going for explicitly evil or man-eating giants, one could plausibly and amusingly have giants with exactly the same reaction to human beings around them. What if a giant just thought you were kind of adorable, and didn't really see you as a serious being?

Now, there are some narrative issues with this, the biggest one is that protagonists often really don't like being talked down to. Nonetheless, especially for a lower level group where they don't pose any threat to the giant, this does make for a narratively interesting problem: it may well be that the giant has something that you need, or can do something that you can't, on account of being a giant, but how do you persuade them to help you? What does a giant want, and how can you get the giant to take your request seriously? Perhaps indeed they never do take you or your request seriously, and you have to find some way to get them to treat it as playing along with your "little game".

I feel that we're sometimes insufficiently imaginative in the threat that bad giants pose. The tendency is that the threat of the giant is direct and physical - the problem is that the giant wants to eat you. Sometimes there's also a power structure issue: the king is, or has, a giant and you need to defeat it, David and Goliath style.

But societal power and direct murder aren't the only ways that a giant's strength can allow them to be a threat. Think of the various things humans need for life - whether that's water, food, shelter, company - and it quickly becomes obvious that, especially for resources that are already stretched, the power of a giant can simply be in denying resources to other people. This could be either unintentionally, perhaps we can't hunt because the giant is eating all the wild oxen, or entirely intentionally, if say the giant has a hidden cave that only he has the strength to open the giant door of, and he keeps a key resource hidden in there and forces people to do things for some limited access to it.

This particularly struck me in the Somali myth of Xabbed ina-Kammas and Biriir ina-Barqo, where Xabbed, the evil giant, doesn't eat people, and he doesn't - he just uses his prodigal strength to put giant rocks over all the wells in the area and then extorts camels from people to eat, only allowing them access to their wells if they provide him with food. This is a really interesting way of playing the giant, one that recognises and emphasises his incredible strength, but without him being reduced to a symbol of brute force. We're more uncomfortably reminded in Xabbed's story about very human ways of using power and strength to extort, rather than simply as brute force, and that can very effectively set the giant as villain apart from other monsters and make their role more individual.

We accept the idea that giants are larger than life versions of things we do as humans, but often this is restricted to general traits - like appetite, or boastfulness - or to roles in kingship or war, where the giant's prodigal strength could be seen as a natural qualification. But we can also scale up other traditional roles and embody them in giant form. We could have a mother-giantess that looks after the women of a particular valley, or a smith-giant who teaches the craft to young artisans, or a woodcutter giant who lives out in the wilds and watches out to help those who venture into the woods alone. A particular inspiration for this is the Musgoso, a giant from northern Spain, who is a "shepherd of shepherds" and looks after the herdsmen on the mountain hillsides, being called upon when they are under threat.

We often give these sorts of hyper-embodiment roles to elderly characters - but giants, great in size where the elderly characters are great in age, can also work well for them. Much like an older character's age, a giant's size can set them in a somehow magnified position, and give them an easily visible hook that displays why they in particular have this role. Some roles don't work well for this - especially those that rely on nimbleness or dexterity, so a giantess as the embodiment of roguery and theft probably isn't on the cards. Nonetheless, if our characters are going to go and seek help or take an NPC to the master of their craft, having that character be a giant can be an interesting and less immediately common way of setting them apart and one that, because the scaling up of the giant's size somehow logically fits with the scaling up of their societal role, oddly does work on an intuitive level.